The Fishwives March! On the Historicization of Women in the French Revolution

/An infamous story so thoroughly chronicled and widely dispersed within Western culture, the French Revolution is a behemoth. Its events have been theorized and reworked from thousands of angles, suppressed and ignored by dozens of historians, presented by handfuls of disciplines, and made to benefit hundreds of agendas. Focusing on a gender-specific action, the women’s march on Versailles, this essay hopes to provide a case study of the complexities of storytelling writ-large, and deny the trusted foundation of linear time that the authoritative discipline of History works through. As stories are told each iteration holds its own. Today, the story of the women’s march on Versailles sprouts up as the hydra’s new head.

The Women’s March on Versailles

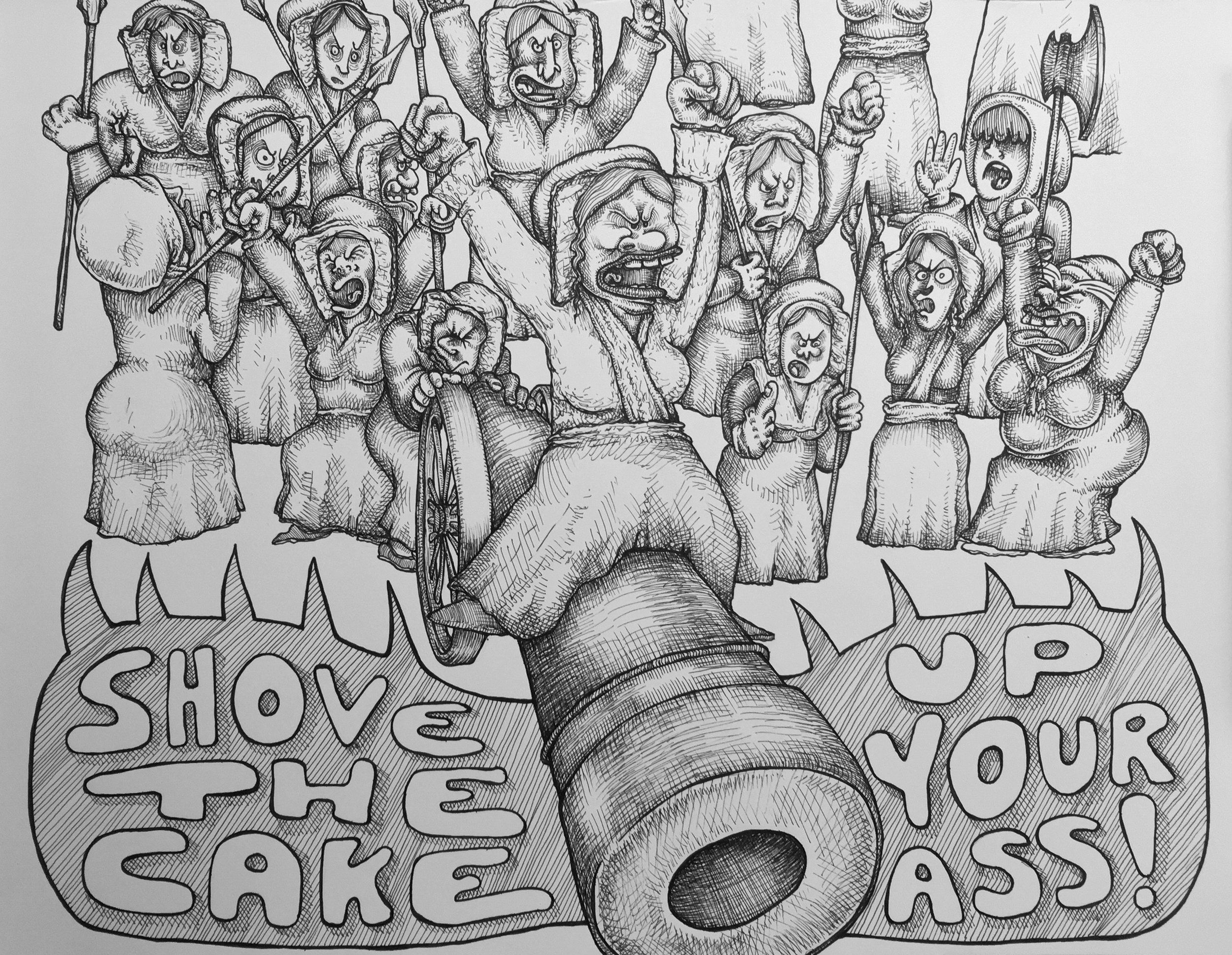

On the morning of October 5th 1789, 7,000 women gathered outside the Hôtel de Ville [1], the seat of the city government in central Paris, demanding the release of the city’s bread supplies. Led by the fishwives and fruitsellers of Paris, they came from different quarters of the city, gathering arms and supporters as they went.

By noon, lacking any response from the Commune [2], the crowd elected to set out on the twelve-mile march to the Palace of Versailles in the rain. They were armed with pikes (long spears–up to twenty-five feet), muskets (.69 caliber, long range, single-shot rifles), scythes, and a small cannon they stole from the Hôtel de Ville. Their goal: to alleviate the food crisis plaguing le peuple, by way of pressuring King Louis XVI and the people’s governing assembly [3], to address and alleviate the food crisis. According to a first-person testimony, the women “did not want any men with them… [and] reiterated repeatedly that the [Commune] was made up of aristocrats.” [4]

Social and Financial State of France on the Eve of the French Revolution

Since the mid–17th century, during the reign of the Sun King, Louis XIV, the monarchy had continuously been funding continental and imperial wars. By 1789, France was essentially bankrupt. Half of the National Treasury was being allocated solely to the repayment of debts that France had accrued funding these wars and an ever-growing army. A rise in population made matters worse. Between 1700 and 1780, the population of France grew from 20 to 28 million, due to a decrease in diseases like the bubonic plague and modern medical advancements, people were living longer, healthier lives. But, agricultural production had not kept up due to several years of poor harvests. [5] In 1789, Paris recorded its 57th straight year of frost, as well as one of the coldest winters. Descriptive reports of orchards dying and food stores spoiling were common. This same year, the price of a four-pound loaf of bread rose from 9 to 14.5 sous, while unskilled laborers were earning no more than 20 sous a day. The working poor in the cities shouldered these conditions most directly, experiencing widespread hunger and debt.

The common people, who were not born into nobility or members of the clergy, made up the Third Estate, and 98% of the population. They concentrated their activity in the center of the city, living and working in a crowded maze of streets on the Île de la Cité or close to the central market at Les Halles, and in the neighborhood of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine, in the east of Paris. In the years leading up to the Revolution, these neighborhoods saw a significantly marked influx of thousands of unskilled immigrants from poorer regions of France, causing severe overcrowding.

The living conditions were horrific: most workers and their families lived in cramped, dirty, and uncomfortable rooms they shared with other families. Due to a lack of plumbing, water was carried in from communal wells outside. Toilet facilities were also located outdoors, in the form of cesspits or open sewers. In spite of Enlightenment-age medical advancements, these conditions led to rampant disease and death in the city, and children often did not survive past the age of ten. [6]

Emile Bayard, Young Cosette Sweeping, 1886. Engraving for Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables.

The Fishwives Make the Rules: Roles of Market Women in Everyday Parisian Life

The bustling food shops and markets filled Paris’ social and geographic center. Here, both customers and sellers were predominantly women, and their numerical dominance gave them a key local function and measure of control. A person seeking directions or looking for someone, for example, would ask a woman selling flowers or cabbages in the street, since she would have been plugged into daily life, and known everyone and their whereabouts. [7] The unique sociality of these spaces allowed for the expedited spreading—or broadcasting—of news and ideas, as well as the creation and proliferation of a tight-knit, female-dominated community.

Apart from being knowledgeable of the happenings of the city, the market women enacted a certain amount of influence on local affairs. They would step in physically when necessary, generally coming to the defense of the vulnerable. At the central market, Les Halles, these women were notorious: “les poissardes font la loi” (the fishwives make the rules), wrote observer of Parisian life, Luis-Sebastien Mercier. [8] They led revolts against bailiffs and police when they were arresting beggars or debtors. Bruised police agents recalled a woman selling fruit who had excited the populace to attack them when they tried to arrest a beggar on the Rue de Saint Paul. [9] When Jacques-Louis Ménétra was a boy in Paris, his father came to beat him for some misdemeanor, but the market women came together and jeered at him. The boy got no more than a telling-off that day. [10] These women upheld a moral code in a domain that was their responsibility.

Already under the Ancien Régime , the monarchical system in place in France since the Middle Ages (c. 1400–1792), the activities of women often crossed over the fluid boundary between public and private spheres. Food supply, although a political and public matter, was broadly accepted as a legitimate area of women’s action; in some cases, one in which women had the primary responsibility to respond.[11] Historian David Garrioch explains, “Although they were intervening in the ‘public’ domain, it was not an intrusion. They were on their own ground, and their action was very much a part of women’s function in the city in safeguarding the family and the local community.” This positioned them at the center of community life.

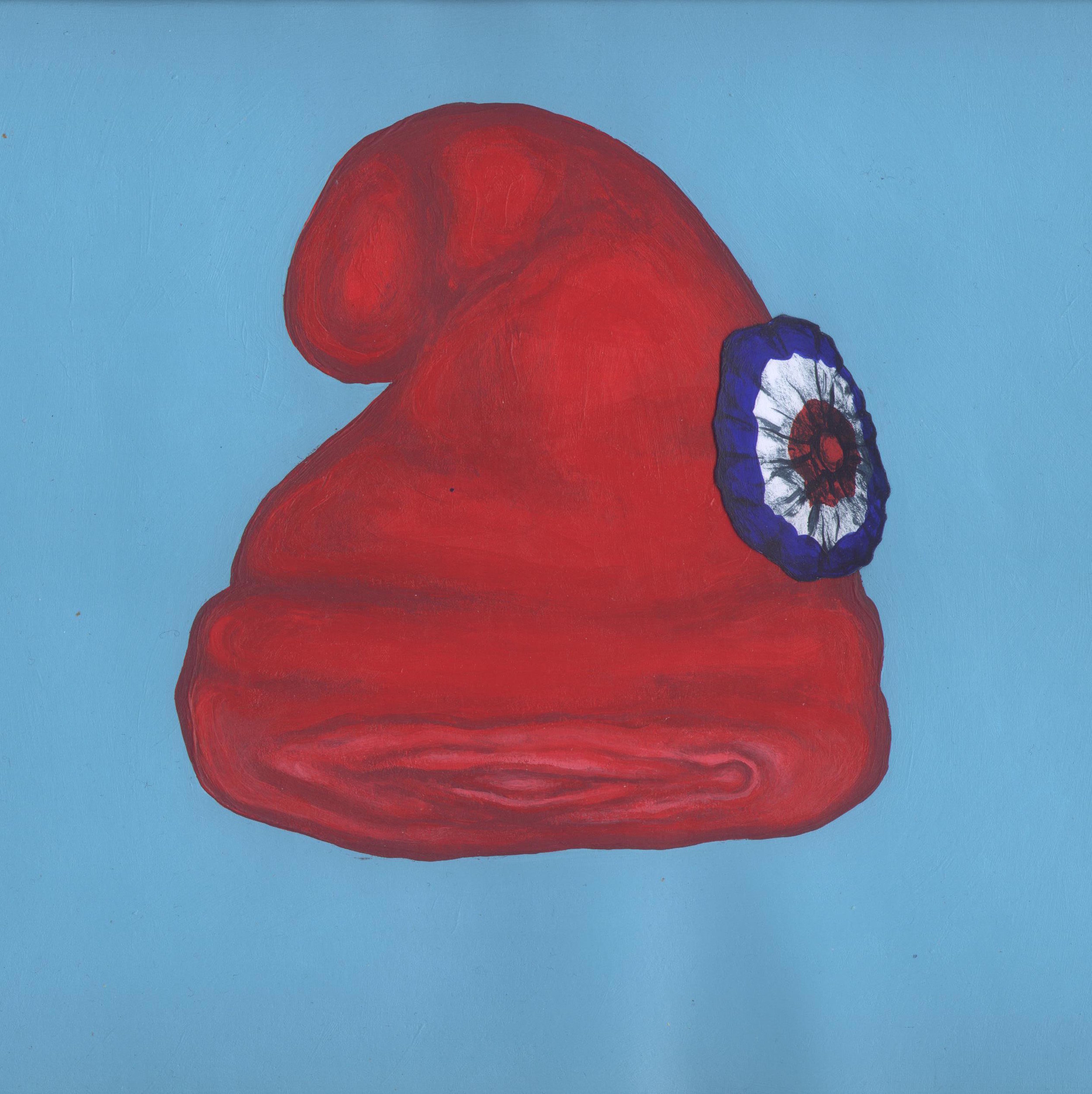

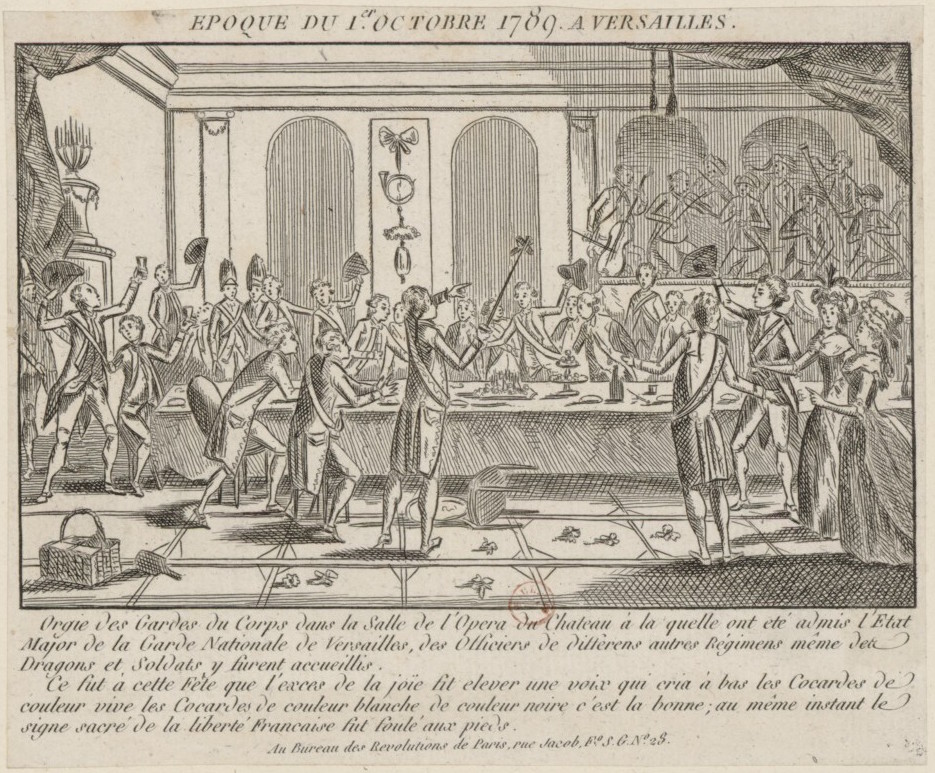

Meanwhile, the king and court were enjoying extravagant lifestyles at the palace of Versailles, as popular culture, specifically Hollywood film, has portrayed in great detail. One particular event struck a nerve with the working poor. On October 1st, the royal court threw a welcome banquet for a regiment of soldiers who had come from Flanders to strengthen the king’s bodyguard. If the news of a lavish feast was not insult enough to the starving people, it was rumored that later in the evening, after drinking and celebrating for hours, the soldiers threw their tricolor cockade pins, a symbol of the Revolution that they were publicly supporting, onto the floor, then continued to stomp and urinate on them.[12]

Illustrations generously provided by Flo Pizzarello (b 1986, Buenos Aires, Argentina), and artist who lives and works in San Francisco, CA. She received her BFA from the University of North Texas in 2013, studied at the Instituto Universitario Nacional del Arte in Buenos Aires from 2006-2010, and received an MFA from San Francisco Art Institute in 2015. Her work has been exhibited in various locations such as Asofnow Gallery, The Fort Mason Center, Submission Center for the Arts, No Roof Gallery, and 500x gallery. http://www.flopizzarello.com/

These rumors were circulated through pamphlets[13] and other short publications like libelles, short stories, plays, or images that depicted public figures in a pornographic or crude nature.[14] According to Jean-Paul Marat’s pamphlet L’Ami du Peuple (Friend of the People), some officers even donned the black and white cockades, which represented the Ancien Régime, all while Louis XVI watched in amusement.

Marchons! Marchons! The October Days Continued…

By October 4th, the people had taken to the streets of Paris in protest, and by October 5th, the situation became overtly political. As the mass tramped to Versailles, it grew in numbers and their demands multiplied. [15] The leaders of the action wanted the monarchy to address the food shortage, but others called for the king to relocate to Paris and reign with his people.[16] Some who joined the march did so only to harm the king, and they were not only women but also men.

They arrived at Versailles, where the court members were seeking refuge in their apartments, behind locked gates. Some of the group broke into the hall where the National Assembly was meeting. Six women[17] were deputized, so they were able to enter the palace and plead their demands to the king. A diplomatic exchange resulted in a promise by King Louis XVI to release the grain stored in royal reserves. He also signed the new reformist legislation The Declaration of Rights of Man and Citizen, which provided protection for numerous individual rights such as liberty, property, freedom of speech and the press, freedom of religion and equal treatment before the law. [18]

But, the women who started the march—a more radical section of the crowd—didn’t believe the king. Around dawn on October 6th, they snuck into the palace through an unguarded side entrance, and stormed through the palace halls. A soldier opened fire on the mob, and killed one its members. In retaliation, the women dismembered and killed two of the guards.[19] Terrified for his life and trying to calm the people, the king, wearing a tricolor cockade, addressed the crowd from a window balcony: “My friends,” he told them, “I shall go with you to Paris, with my wife and children. It is to my good and faithful subjects that I confide all that is most precious to me.”

Escorted by a procession of 30,000 successful activists, the king, queen, and members of the National Assembly headed to Paris that afternoon,[20] where they were installed in the dilapidated Tuileries Palace.[21] The king became a prisoner of the Revolution, never to return to Versailles. The October Days’ march propelled the revolution forward and further radicalized the socio-political climate. The march was a triumph over not only absolutism, but the king himself, preventing the last-ditch royalist attempt at counterrevolution and firmly entrenching the Revolutionary victory of 1789. It was also cause of the royal family’s move to Paris, making them recognizable to the general population, which prevented them from escaping when they tried to flee to Austria. Marie Antoinette, and the king were both executed in 1793.

Epoque du 6 octobre 1789, l'après diné, à Versailles : les héroïnes françaises ramènent le roi dans Paris, pour y faire sa principale résidence, S. M. était escortée de la Garde nationale, d'une partie des Gardes du corps, et du Régiment de Flandre, stamp, 9 x 14 cm. Collection Carl de Vinck and Michel Hennin. Bureau des Revolutions de Paris, [1789]. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb40249176b

The October Days’ March was indisputably a gender-specific action of large proportions, and immense consequences. While most textbooks and detailed accounts of the French Revolution document the event, there is little preparation or background information to contextualize it. These common women demonstrated a political awareness and a capacity for independent political action, but despite the women’s success and the impact of the event, the story appears suddenly.[22] Without knowledge of the market women’s community roles and responsibilities, one might ask: How were these women, who almost certainly possessed less formal education than their male peers, who were excluded from the National Guard and who in general were less of a target for political journalists than the men, able to go beyond anything that men had attempted? And how did they do so at this very early stage in the Revolution?

Academic writing, historical documents, and contemporary media systematically position the political action of women[23]—when it comes up at all—as abrupt, instantaneous, and astonishing. The context of any political action—the cultural, social, and political factors leading up to the protest, march, battle—is not only a part of the action, but defines it. If a movement crops up out of nowhere, it is left vulnerable to revision and discrediting, and it is likely to suffer an immature death.

The French Revolution is extensively historicized, studied closely, and written about at length by scholars, novelists, high school students, and history buffs.[24] Most literature that mentions women at all has been primarily devoted to proving the nature and extent of female involvement, rather than explaining it. Moreover, most writers have been more interested in the work of the women’s clubs of I793, which were organized by wealthy women much later in the Revolution.[25]

From the 1970s onward, feminist historians such as Jane Abray, Darline Gay Levy, Harriet Branson Applewhite, Mary Durham Johnson, and Joan Landes began to look at the role of women in the revolution, who were ignored or marginalized in earlier histories. As exhausting as it may seem, it takes many stories to counteract the assumption that Revolutionary women only acted as hysterical, furious mobs, and that the October Days’ actions were politically motivated and independent. Even in the court records documenting the Revolutionary trials in 1790, most of the women who had participated denied any role in the violence, as they feared being implicated. Their depositions were also often co-opted by men, used to secure them more power in the changing political system, or save them from the guillotine’s sharp blade.[26]

Stories live in this way—between and among us, shifting as they are expropriated and leveraged by a myriad of power structures. Even our “contemporary” political events, such as the 2017 Women’s March on Washington exist in multiple forms, i.e. Donald Trump’s underestimation of the number of attendees; the criticism responding to a lack of intersectional representation; the letters written in marker on handmade signs; the data analysis of attendee numbers conducted in the form of a digital spreadsheet tally of attendees presented, and painstakingly, but necessarily validated by a pair of political science professors.[27] This multiplicity is often overwhelming in the present.

History is imbued with authority (usually by the state) and distanced from our present so it might appear as a cohesive and factual. But, even the legitimized chronicles of times past function within the same multiplicitous form as current, topical events. Each political, cultural, and psychic iteration is as valid as the next. There is no point now in fixing an origin of fact, as we know, even primary documents have without doubt been commandeered, even as they were recorded. In its varying iterations, the story is many, constellatory, affective, functioning outside of a linear understanding of time.

-

The seat of Paris’ municipal headquarters since 1357 in the 4th arrondissement, the civic building houses mayoral government that is systematically and symbolically represents the French state. It is abutted by a large square. The building was later captured by Revolutionary forces and served as the headquarters of the Revolutionary government. ↩

-

The Paris Commune, the newly formed city government, had established itself at the Hôtel after revolutionary forces stormed the Bastille prison a few months earlier. ↩

-

The Assemblée Nationale Constituante, or the National Assembly, was the governing assembly of France from 1789–1791. This group was born out of the Third Estate, who wanted to distinguish themselves from the other two estates with their name and function, though the group was led mostly by the wealthy, who wanted more rights, despite their lack of noble blood. Honore Mirabeau and Maximilien Robespierre were among the more well-known and active members. (“The Third Estate,” “France”) Le peuple, or the people, is a reference to a collective group of people that was used during the French Revolution. The terms “crowd” and “mass” were employed later, to be more specific (Censer, Hunt, 38). ↩

-

The women were reported to have said, “that it was all that had been done since the Revolution had begun and that they would burn them … these women repeated that the men were not strong enough to avenge themselves and that they would show themselves to be better than the men.” Police agents reported similar declarations: “The men are holding back, the men are cowards … we will take over.” (Bibliothèque nationale, Paris [B.N.], Mss. 6680. ↩

-

France’s food supplies were affected by poor harvests in 1769, 1770, 1775, 1776, 1782, 1783, 1785, and 1788. Various factors including drought, hail storms, volcanoes erupting, and frost. All contributed to the insufficient amount of grain harvested. ↩

-

Yves Blayo, 1975, “Mortality in France from 1740 to 1829,” Population, vol. 30, n° special, p. 123–143. ↩

-

This was before the appearance of the concierge—who only became a common figure at the very end of the eighteenth century (Garrioch, 241). ↩

-

Louis-Sebastien Mercier, Tableau de Paris, 12 vols (Amsterdam, 1782–8), VI, 306. A good English translation of Mercier’s study of urban city life is Panorama of Paris: Selections from Le Tableau de Paris, edited by Jeremy D. Popkin. ↩

-

Archives Nationales, Paris, Y15350, 5 June 1752. ↩

-

J.-L. Ménétra, Journal of my Life, D. Roche (ed.), trans. A. Goldhammer (New York, 1986; first published Paris, 1982), 38–9. ↩

-

Religious activity, was another public activity in which women were the primary regulators, and encouraged a sense of identity. One way that this was realized was through the public devotion of the statues on street corners. For example, it was mainly women who flocked to pray beneath a statue of the Virgin in the Faubourg Saint Antoine in I752 when its head was rumored to have turned from one side to the other (Garrioch, 240–241.) ↩

-

The tricolor cockade is a tight knot of colored ribbons that was pinned to one’s hat, tunic, lapel or sleeve. It was among the first symbols of the French Revolution After the fall of the Bastille, in July 1789, the white of the Bourbon monarchy was joined to red and blue colors of Paris to create the new tricolor symbol of the nation, which would appear on flags, banners, and sashes as well. After the October Days, the tricolor cockade gained further notoriety as a symbol of revolutionary patriotism (Hanson, 72). ↩

-

With the fall of press censorship in mid-July, a booming newspaper and pamphlet press developed, often taking up debates over the early National Guard. In 1789, images of Queen Marie Antoinette were most popular. ↩

-

There has been extensive research conducted on this subject. See Lynn Hunt’s The Invention of Pornography, 1500–1800: Obscenity and the Origins of Modernity, 1993. See the index, available here for more: https://books.google.com/books?id=OsAjDQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=french+revolution+pornographic&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiUtdKEyuLZAhUP8GMKHVIZA-gQ6AEILjAB#v=onepage&q=french%20revolution%20pornographic&f=false ↩

-

An account of the October Days by Adrien Duquesnoy recalls that “ten, twenty, thirty thousand people were coming to Versailles, intent on seizing the king according to some, seeking to force the [National] Assembly to hasten its work, according to others.” ↩

-

It is important to note that most of the working poor did not blame the king directly for these problems, and still felt an allegiance to him. If blame were to be placed on any one figure, it would be Marie Antoinette. There was still an allegiance to the king, and a general belief that if the king knew the extent of the food crisis and how it was being felt by the people, he would not approve. There was an awareness of the complex political situation, and a hope that the king’s return to Paris would restore his image of a good father, taking care of his patrimony. ↩

-

The number of women who entered the chateau vary, as do most accounts of political action in the French Revolution. Fournier’s, for instance, says fifteen women plead their demands to the king while Rose-Barré’s deposition describes only four women. ↩

-

This document is often considered the most important legacy of the French Revolution, more universal, general, and fair than the United States’ Constitution. It marks the end of an absolutist monarchy while providing a model for future societies seeking freedom and self-government, in which all people—women, slaves, those without property—were guaranteed these natural rights. ↩

-

This is when it is rumored that Marie Antoniette said, “Let them eat cake,” but that didn’t happen. Edmund Burke, an 18th century British historian who has been most widely criticized for his portrayal of the women involved in revolutionary efforts, describes this scene as one of madness, that the women were ready to tear Marie Antoinette to shreds. This hysterical, mad, and senseless presentation of the October Days events is something I am trying to avoid, as the accounts cannot be verified (as with all history), but also deny the pointedness of the political action and relegate the action of women to something happening more by chance, or only based on emotion. ↩

-

Georges Lefebvre, noted 20th century historian, describes the scene in The French Revolution From its Origins to 1793, first published in 1930: “At one o’clock the bizarre procession set out. The National Guards first, with bread stuck on their bayonets; then wagons of wheat and flour garnished with leaves, followed by market porters and the women, sometimes sitting on horses or cannons; next the disarmed bodyguard, the Swiss, and the Flanders Regiment; the carriages bearing the king and his family with Lafayette riding beside the doors; carriages of one hundred deputies representing the Assembly; more National Guards; and finally, the crowd bringing up the rear. They forged ahead willy-nilly through the mud. It was raining, and day gave way to night at an early hour. Insensitive to the gloom, the people, appeased and confident for the moment, rejoiced in their victory. They had brought back ‘the baker, the baker’s wife, and the baker’s boy.’” ↩

-

On their return to Paris, the royal family was installed in the Tuileries, a dilapidated palace not used as a royal residence for decades. Some furniture, clothing and other royal belongings were carted from Versailles to the Tuileries; even so, the royal court in Paris was much more austere. Versailles was maintained, an acknowledgement that the king might someday return, however neither Louis nor his family would see the splendor of Versailles again. The National Constituent Assembly also relocated to the Tuileries, its sessions held in the Salle du Manége, an indoor hall used for riding lessons. ↩

-

“The momentous march of women to Versailles,” says Joan Landes, “can be situated within a long tradition of women’s participation in popular protest.” (Joan Landes, Women and the Public Sphere in the Age of the French Revolution, Ithaca and London, 1988, 109.) Darlene Levy and Harriet Applewhite insist that the actions of eighteenth- century women displayed “political motivation, political awareness, and a certain modicum of political skill … they understood how political power operated to affect their livelihoods.” They suggest, in passing, that the development of the centralized state placed increasing pressure on ‘common women’ across the eighteenth century, and that this contributed to their politicization.” (Levy, Applewhite, 10–12.) ↩

-

Of course there are many different groups whose histories have been systematically denied proper contextualization, if not visibility at all. I am referring to women’s action here as a case study, without extending the processes of the historicization of the October Days’ events to other groups. ↩

-

The earliest record is Edmund Burkes’ Reflection on a Revolution in France published in 1790, which has been widely criticized as overly dramatic in language and tone, and lacking any meaningful attention to the women involved. It was a conservative reaction to the Revolution by an Englishman, who was surprised by the positive feedback it was receiving. ↩

-

Garrioch, 233. ↩

-

Levy, Darline Gay, Harriet Branson. Applewhite, and Mary Durham. Johnson. Women in Revolutionary Paris, 1789–1795. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1980. ↩

-

Another story is the march’s name change from “The Million Woman March,” once organizers realized that black women had organized and marched under that very name in 1997. The Million Woman March took place in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and intended to help bring social, political, and economic development and power throughout the black communities of the United States, as well as to bring hope, empowerment, unity and sisterhood to women, men and children of African descent globally regardless of nationality, religion, or economic status. For further information, visit their website: http://millionwomanmarch20.com/about-us/. Women’s March Protest Count (https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/01/womens-march-protest-count/514166/.) ↩

BIBLIOGRAPHY

"Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot." The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.” 2008. Library of Economics and Liberty. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/bios/Turgot.html

Beik, William. “The Violence of the French Crowd from Charivari to Revolution.” Past & Present, No. 197 (Nov., 2007), pp. 75-110, Oxford University Press, on behalf of The Past and Present Society. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25096691.

Blakemore, Steven. “Revolution and the French Disease: Laetitia Matilda Hawkinss Letters to Helen Maria Williams.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 36, no. 3, 1996, p. 673., doi:10.2307/450805.

Burke, Edmund. Reflections on the Revolution in France, published together with Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man. New York, 1790.

Darnton, Robert. "The Forbidden Books of Pre-Revolutionary France." In Rewriting the French Revolution, ed. Colin Lucas, 1-32. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991. DC148.R49 1991.

"Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen." Encyclopædia Britannica. December 15, 2017. Accessed March 12, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Declaration-of-the-Rights-of-Man-and-of-the-Citizen.

Delon, Michel. Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Chicago, IL: Fitzroy Dearborn, 2001.

"French Revolution historiography." French Revolution. January 18, 2018. Accessed March 04, 2018. http://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/french-revolution-historiography/.

"French Revolutionary Wars." Oxford Reference. 12 Mar. 2018. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780191737817.timeline.0001.

Fortescue, William. "Paris Commune." Europe 1789-1914: Encyclopedia of the Age of Industry and Empire, edited by John Merriman and Jay Winter, vol. 4, Charles Scribner's Sons, 2006, pp. 1733-1738. World History in Context, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX3446900628/WHIC?u=sfpl_main&xid=c97f839e. Accessed 10 Mar. 2018.

Garrioch, David. "The everyday lives of Parisian women and the October days of 1789∗." Social History24, no. 3 (October 1999): 231-49. doi:10.1080/03071029908568067.

Hanson, Paul R. A to z of the french revolution. Scarecrow Press, 2007.

Hays, J. N. The burdens of disease: epidemics and human response in western history. W. Ross MacDonald School Resource Services Library, 2012.

"History." Palace of Versailles. February 08, 2018. Accessed March 11, 2018. http://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/history#the-19th-century.

Holloway, S.T. “Why This Black Girl Will Not Be Returning To The Women’s March.” Huffington Post. 2018. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/why-this-black-girl-will-not-be-returning-to-the-womens-march_us_5a3c1216e4b0b0e5a7a0bd4b

Hunt, Lynn, and Jack Censer. "Imaging the French Revolution: Depictions of the French Revolutionary Crowd." The American Historical Review110, no. 1 (February 2005). doi:10.1086/ahr/110.1.38.

Kropotkin, P. (1927). The Great French Revolution, 1789-1793 (N. F. Dryhurst, Trans.) New York: Vanguard Printings. Ch. 4.

Leebaw, Bronwyn. "Inventing Human Rights: A History - by Lynn Hunt." Ethics & International Affairs22, no. 1 (2008): 119-21. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7093.2008.00133.x.

Levy, Darline Gay, Harriet Branson. Applewhite, and Mary Durham. Johnson. Women in Revolutionary Paris, 1789-1795. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1980.

Levy, Darline Gay. The Journal of Modern History 72, no. 3 (2000): 805-07. doi:10.1086/316067.

Levy, Darlene Gay . "The Women of Paris and Their French Revolution. By Dominque Godineau." Edited by Lynn Hunt. Studies on the History of Society and Culture26 (1998): 805-09. doi:10.1086/ahr/104.3.1007.

"Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution, With 12 Topical Essays, 250 Images, 350 Text Documents, 13 Songs, 13 Maps, a Timeline, and a Glossary." Liberty, Equality, Fraternity: Exploring the French Revolution. Accessed March 04, 2018. http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/.

Llewellyn, J. and S. Thompson. "Harvest Failures." Alpha History. http://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/harvest-failures/.

Llewellyn, J. and S. Thompson. "The October March on Versailles." Alpha History. 2015. http://alphahistory.com/frenchrevolution/october-march-on-versailles/

Maillard, Stanislas, “Stanislas Maillard’s testimony to the Châtelet Commission,” Procédure criminelle instruite au Châtelet de Paris, 2 vols. (Paris, 1790), vol. I, pp.117—32, reprinted from George Rudé, ed., The Eighteenth Century (New York, 1965), pp. 198-205.

Neymarck, Alfred. "France, 1789-1889. An Economic Centenary." Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 52, no. 2 (1889): 306-38. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.sfpl.org/stable/2979334.

Nora, Pierre. "Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire." Representations, no. 26 (Spring 1989): 7-24. Accessed March 10, 2018. doi:10.2307/2928520.

Nygaard, Bertel. “The Meanings of “Bourgeois Revolution”: Conceptualizing the French Revolution.” Science & Society, vol. 71, no. 2, 2007, pp. 146–172. JSTOR, doi:10.1521/siso.2007.71.2.146.

Pernoud, Georges and Flaissier, Sabine. The French Revolution, translated by Richard Graves (New York: Capricorn Books, 1970), 61–66.

Rose, R. B. "Feminism, Women and the French Revolution." Historical Reflections / Réflexions Historiques 21, no. 1 (1995): 187-205. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.sfpl.org/stable/41299020.

Roche, Daniel. “The people of Paris: an essay in popular culture in the 18th century.” University of California Press, 1987. p. 10. Retrieved 2016-02-10.

"Stanislas Maillard describes the Women's March to Versailles (5 October 1789)." 2001. Accessed March 12, 2018. http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/473/.

"The Women's March on Versailles" 8 February 2017.

HowStuffWorks.com. <https://www.missedinhistory.com/podcasts/womens-march-versailles.htm> 4 March 2018

Turgot, Anne-Robert-Jacques. Reflections on the formation and distribution of wealth. Department of Economics, McMaster University, 2004.

Zerilli, Linda M. “Text/Woman as Spectacle: Edmund Burke’s “French Revolution.” The Eighteenth Century, Vol. 33, No. 1 (SPRING 1992), pp. 47-72. University of Pennsylvania Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41467765

Kathryn Barulich is an independent curator, writer, and researcher. Her research interests focus on how nationalism and language influence contemporary visual culture and politics. In 2015, she completed a Masters degree in History and Theory of Contemporary Art from San Francisco Art Institute, after studying French and Art History at Fordham University. She works at several arts organizations in the San Francisco Bay Area.