Footnotes on the Ostrich Feather Wedding Dress Project: Wearing the Beast

/Footnotes is a project by Christopher Squier of studio visits and artist interviews. It examines the spaces and detritus of artists’ studios to ground discussions of artwork in their process, references, and inspiration.

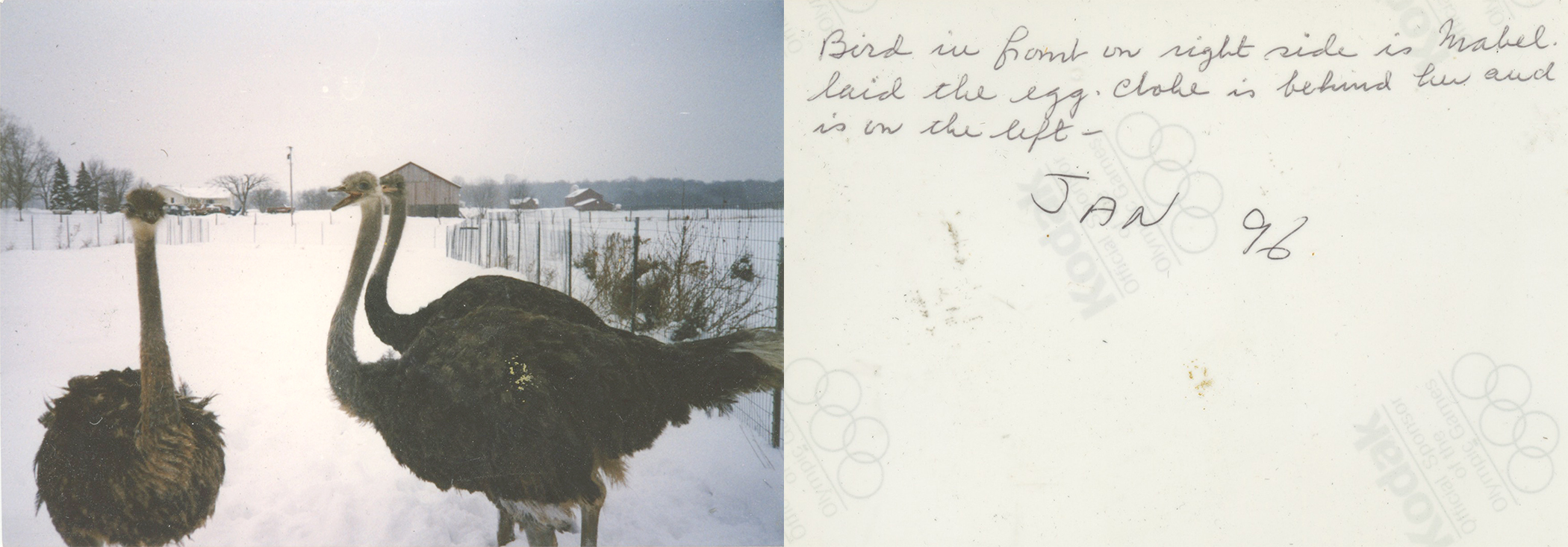

Photograph of ostriches in Ohio, 1996. Image courtesy of Lorna Stevens.

For Joanne Easton and Lorna Stevens, a secondhand wedding dress purchased on eBay became the beginning of an exploration that grew to involve over a dozen new interpretations of the dress on the themes of constructed gender and marriage ideals, fetish, and fantasy.

The garment is not the minimal, antiseptic gown of orthodoxy, but its wild cousin. Festooned with an unruly, downy border of snaking, white ostrich feathers engulfing the neck and wrists, drooping sleeves and an empire waistline, the dress makes space for new variations on a historical theme. In the Ostrich Feather Wedding Dress Project (OFWDP), Easton and Stevens reposition the wedding dress alongside the unusual secondary object of the ostrich egg, underscoring its role as an icon to explore the ambiguity inherent in signifiers—the physical form of a sign, as distinct from its meaning.

Balloons and ostrich egg displayed in the studio of Joanne Easton, 2016. Photograph: Christopher Squier.

The image of the wedding dress is a ghostly one, one which echoes through pop cultural imagery and leaves traces—much as Easton and Steven’s dress leaves behind feathers in each of the places it is taken. Throughout pop culture, the wedding dress cycles through the iconography of advertising, film, and literature, producing in each case new iterations of marriage and new notions of the family as a social, cultural, and political ideal. Conversely, it is a symbol that is scapegoated within the classic American family drama, made ragged by the omnipresence of divorce, and turned upon within conversations of civil discrimination. The image of the wedding dress serves as an effigy to the larger concept of marriage, and its status as effigy could be described as the sum of its soured promises. At the very least, the symbol of the wedding dress is a charged one, fraught with the aspirations and failures of the ideal family in its many forms.

It is also an image that implies another: the wedding dress is part of a union, a collaborative struggle, or part of a pair. It is never singular. Instead, it is the link between a bride and a groom or a bride and a bride and, by extension, it is the node around which new families are cemented (as with relatives and in-laws) and imagined (as with children). Even through its negative connotations, it implies the actions of others (a failed marriage begets assumptions of duplicity, disloyalty) and their role in a shared social drama. In the case of the ostrich feather dress, it goes further to invoke the bird behind the dress, the ungainly, powerful creature whose feathers were used.

Collected objects on a work desk in the studio of Joanne Easton, 2016. Photograph: Christopher Squier.

Easton and Stevens take up this potential of the traditional wedding dress as social and familial link throughout their project, inviting new unions and collaborations. Their gesture is to present their colleagues—other artists—with the dress and wait for a response. Easton and Stevens invited thirteen artists to respond to the dress as a material and symbol: its textures, terrors, and broader connotations. The results were mounted last November in the exhibition Common Dilemmas at Gallery Route One.

In the process, the project became an experiment in a symbol’s potential to shift its meaning across contexts, uses, and purposes and to become newly defined, enigmatic, or irregular through the transformations of the artists involved.

Loose feathers in the studio of Joanne Easton, 2016. Photograph: Christopher Squier.

Interview with Joanne Easton and Lorna Stevens

CS: In your exhibition Common Dilemmas, the ostrich eggs and the feather dress serve as markers of our relationship with the actual animals they are gathered from. What is it about the ostrich and endangered birds that initially caught your interest?

JE: Human relationships with the natural environment have been an element in both our work. I was fascinated by how this animal seemed to be represented. There are ostrich pillows, cartoons of the ostrich with its head in sand, and its feathers adorn Forever 21 skirts and high-fashion coats. Somehow it has been cast a gangly funny beauty. All of these aspects are human perspectives. [It] turns out the ostrich does not put its head in the sand when it is scared. It is simply turning and protecting its eggs, which it does several times a day. I am interested in these relationships of power. What is a way of living that lives with the environment and its animals, not on the environment and its animals?

LS: I’m interested in visually commenting on dubious human behavior, especially in response to the natural world. Obliterating a species for its plumage seems shortsighted and dumb, yet our history includes many such examples. Jo and I researched why the ostrich survived despite intense demand for its feathers, skin and meat. We learned that size, speed, inability to fly and adaptability to farm raising were factors. We approached working with the eggs mindful of these facts.

JE: I find it interesting that the white feathers, like the ones on the dress, are from the male ostrich. The female ostrich has mottled brown feathers.

Marcela Pardo Ariza, Between the Scalpel and the Ring, 2016, 11 x 16 inch, archival inkjet print. Image courtesy of Lorna Stevens and Joanne Easton.

CS: What was the process for the delivery, handing off or passing on of the dress to each artist?

LS: We each invited artists we felt would respond well to the dress and we took responsibility for arranging, delivering and picking up the dress from those artists, though if Jo was out of town, I’d step in and vice versa. Artists were invited to keep the dress for a week, though some wanted to keep it longer and others needed less time. We kept a calendar in Dropbox chronicling the whereabouts of the dress.

JE: I wish we had taken pictures of the handoffs. Lorna and I arranged times and places to meet each of the artists. Many times this was en route somewhere. Sometimes artists were able to transfer the dress to each other and therefore meet if they had not before. A favorite transfer was the handoff from Lorna to Marcela [Pardo Ariza]. I was out of town and Lorna who had not met Marcela before was able to meet up with her. This was great because they got to meet and chat and transfer the dress. The second best part was Marcela taking off with the dress in her bike basket. I love the image I get from that!

Deflated balloons and feathers in the studio of Joanne Easton, 2016. Photograph: Christopher Squier.

CS: The initial ostrich eggs were from a family farm in Ohio, which might be one origin story for this project. It seems overstated to say that a work of art will inevitably overlap with some part of one’s own personal biography or day-to-day experience. Could you talk about the overlap and divergences in making work with over a dozen people. Did the ostrich feather dress resonate with you or the other artists as you expected it to?

LS: My aunt sent me the eggs in 1996, but they languished on a back shelf in my studio until Jo responded to them when we were looking for materials to begin our collaboration. I needed her to stimulate my interest in the eggs. Similarly, I bought the dress because it intrigued me, but I saw it as a costume. The OFWDP artists, with their rich and varied interpretations, challenged me to expand my understanding of the dress. I heard very few stories of easy going with the dress. Most artists told tales of much meandering from initial thoughts to resolution of their pieces. Both Jo and I are grateful they were willing to take the journey.

Experimental piece in the studio of Joanne Easton, 2016. Photograph: Christopher Squier.

CS: I’m always interested to hear about failures as so much of artistic labor goes unseen in the final exhibition, although ultimately trials and experiments are critical to the development of most strong bodies of work. Did the OFWDP make any notable missteps?

JE: Oh yeah! We had a few false starts with the dress. Lorna mentioned initially she was thinking of using the dress as a prop or costume. We talked to a dancer and to our friend Minoosh [Zomorodinia] about performance directions. But none of that seemed to fit. Exasperated, we went back to the beginning when the dress was funny and full of potential. Lorna had taken a selfie in the dress and we talked about it being a fun experiment to do that again as a photo shoot. Lorna invited her friend and photographer Suzanne Engelberg to her studio to have a photo shoot with the dress. I think that really cemented the idea to free the dress and let other artists respond to it.

Tools in the studio of Joanne Easton, 2016. Photograph: Christopher Squier.

CS: In my experience, it seems like the most valuable thing a project can do is to interrupt existing trajectories to reimagine your present goals, acting in a way as an interlocutor to interrupt habitual routines. Each artist in the OFWDP did an elegant job of adapting their overall practice to include the wedding dress and yet retain some characteristics of their usual work. How do you situate these works and the process of working collectively in relation to your typical studio routine?

JE: For us Common Dilemmas was a tangential practice. It was a blend of freedom to do something I probably would not have and restriction to work with a material within a theme. The project came out of that process. The openness and having the support of my collaborator was invaluable – setting a plan of action but allowing it to wobble and change…. continually.

Katherine Vetne, Glass Orb, 2016, 9x10 inch, silverpoint on prepared paper. Image courtesy of Lorna Stevens and Joanne Easton.

Hadar Kleiman, Feather Flare, 2016, 16 x 16 x 1 inch, vinyl print on plastic laminate. Image courtesy of Lorna Stevens and Joanne Easton.

CS: Many of the works show loose or cut feathers from the dress while others prove that a variety of artists have stepped inside the garment. What’s left of the dress at this point?

LS: The dress is in fine shape. It looked a bit worn after its final studio foray, but was revived by a trip to the cleaners for some sprucing prior to the show. More artists have expressed interest in working with the dress so it will be back on the road again very soon.

Various bird products in the studio of Joanne Easton, 2016. Photograph: Christopher Squier.