Masqueraders: Na Chainkua Reindorf and Simone Leigh at La Biennale di Venezia

/This past year, the Ghanaian pavilion at The 59th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia: The Milk of Dreams featured artist Na Chainkua Reindorf alongside multidisciplinary visual artist and performer Diego Araúja and Nana Isaac Akwasi Opoku, who creates visual art and design under the name Afroscope. The three were part of an exhibition titled Black Star – The Museum as Freedom, the title of which borrows from the national insignia of the Ghanaian state—a black star against a tripartite ground of red, gold, and green. The exhibition foregrounds the black star as a specific icon used across the African diaspora in imagery and language shared by Pan-Africanism, the Back to Africa movement, and the movement for an African global economy epitomized by Marcus Garvey’s steamship corporation The Black Star Line.[1] By invoking the flag in the exhibition’s title and situating these works in a national pavilion at Venice, curator Nana Oforiatta Ayim complicates the role of symbol and sign in relation to the nation state, querying how state forms of regalia, speech, and iconography exceed a nation’s borders to encompass larger ideas and communities. By exhibiting Reindorf’s paintings that reinterpret the tradition of Asafo flags as symbols related to mythic female figures, Black Star goes further to propose a fluid notion of the nation that is personal, gendered, clandestine, and at times subversive.

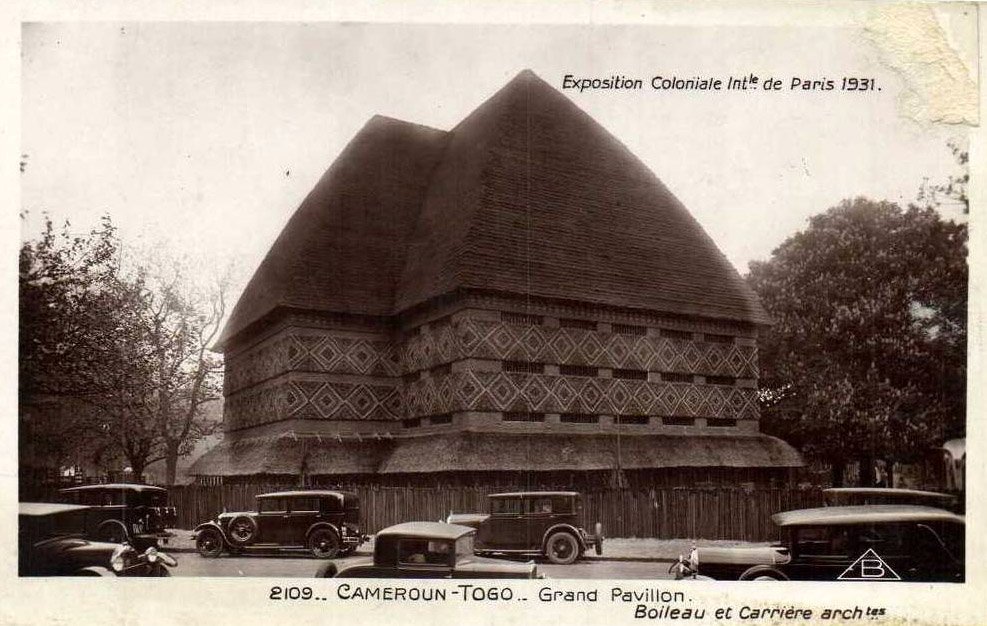

In a related gesture of remaking the national pavilion, artist Simone Leigh’s installation for the US pavilion in the Giardini transforms the exterior façade and gardens of the site into a hybrid form of architecture based in the traditions of Guinean ritual dress, the monumental stoneware pottery of South Carolina’s Edgefield District, and the Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931. In doing so, she refigures concepts of authority and sovereignty in relation to the state and its people by way of myth, scale, and masquerade.

Mawu Nyonu

Na Chainkua Reindorf, Veil, 2022. Glass beads, plastic beads, polycarbonate sheet, fiberglass resin, astroturf, and steel cable. 216 x 180 inches (5.5 x 4.6 meters). Image courtesy of THE Ghana Pavilion, 2022. Photograph by David Levene.

One might recall a famous and often misread[2] section of Roland Barthes’ Mythologies, the canonical work of semiotics in which national/ist ideologies are revealed within the warp of language and in the imagery of everyday life. In one portion of his project, Barthes describes the figure of “a Black soldier … giving the French salute,” whose image produces the myth of French imperial splendor.[3] This soldier is glimpsed in passing while Barthes is at a barbershop; a copy of Paris Match from June–July 1955 crosses his vision and in a flash summons up the formula as follows: a young African man in uniform “is saluting, with his eyes uplifted, probably fixed on a fold of the tricolor.”[4] Barthes goes on to explicate the scene, unearthing in the soldier’s stance myths of nation, empire, and patriotism. While his salute and attempt at a militant pose is indubitable, the “fold of the tricolor” is absent, appearing outside the frame.[5]

The national semiotics of flags have become such regular features of visual culture that they inundate mass media, cropping up everywhere from print advertisements and business logos to commercial videos. Indeed, so forceful and pervasive is the notion of the flag, which cements together national identity over religious, ethnic, and linguistic divisions, that even its implied presence does the work Barthes requires of it. Reading this passage, one might imagine not only the French flag but other possible flags, salutes, and addressees. Where Barthes leaves off his reveries, Reindorf’s begin.

Reindorf’s installation in Venice, titled Mawu Nyonu, includes paintings and sculpture which re-situate our understanding of the status of national architecture and iconography. Reindorf returns to the subversive potential in both the built environment and the garment, reimagining each with the potential for a masquerade. These signifiers and adornments are capable of disguising and refiguring their inhabitant-wearers into powerful personas that live by their own rules. In Mawu Nyonu, a phrase which translates as “God is a woman,” these national and patriarchal forms—pavilion, palace, flag—are revealed as artifices, which are insufficient to the task of representing a people. Through the mystification of these signs within a mythology of her own invention, Reindorf's fictional all-female masquerade society of Mawu Nyonu was born.

The tradition of West African masquerade has provided the structure for much of Reindorf's recent practice since 2016, the year she produced the installation Reveal/Conceal. For that installation, Reindorf constructed two elaborately beaded huts in shades of red and black. Their rounded conical forms and patterning mimicked a number of West African masquerade precedents, like a Yoruba Egungun dance costume she discovered in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum, the helmet-like sowei masks of the Sande Society worn exclusively by women, and the Kakamotobi masquerade costumes worn during the Fancy Dress Festival held annually in the city of Winneba, Ghana.

Na Chainkua Reindorf, Screen, 2017. IMAGE COURTESY OF THE ARTIST.

Another iteration of these same masquerade-costume sculptures, Screen (2017) shimmers with blue-dyed jute fibers topped with plastic and vinyl adornments akin to jewelry; its surface is embedded with semi-transparent mesh screens, which allow a viewer to peep out from inside without being observed, reversing the subject-object roles of a typical viewing experience. This work was produced for Reindorf’s thesis exhibition at Cornell University and responded to the presentation of African masks and artifacts within museums, particularly in a Western context. Whereas masks are often presented in museums for study and observation, Reindorf’s masquerade sculpture was intended to stare back at the viewer. As a visitor entered the gallery, they might assume that Screen was simply a sculptural form, unoccupied by other visitors or viewers. During their approach, the object appears passive, but as they move around it they discover an opening for visitors to enter; if another visitor happened to be inside, it would create an uncomfortable realization of unknowingly having been watched.[6] In a Brechtian move, the actor becomes an observer and the audience the spectacle. Thus, architecture merges with the costumes of the masquerade to become unruly and disconcerting.

As Reindorf writes in her essay “I Am (Not) Myself” for Dissolve, “The masquerades perform as the body, both by entirely concealing it, as would the walls of a building, and as a proxy for that same body it conceals in the onlooker’s perception. I proposed that although the masquerades are entities acting as an architectural space, they could in fact be dresses.”[7]

The figure of the masquerader was popularized during the European Renaissance in cities like Venice and has notably been theorized by the Soviet writer Mikhail Bakhtin. Bakhtin’s writing on François Rabelais proposes a theory of laughter in which the carnivalesque becomes a moment of potential subversion within the everyday hierarchies of established power. As a witness to the derangement of Stalin’s purges, Bakhtin saw something similar in the masquerade days of the Renaissance to “the swirling up of meaning”[8] of the USSR’s more hopeful revolutionary days. He theorized the carnivalesque as one potential form of rebellion against autocratic rule, transgressing the dogmatism of officially-sanctioned speech and providing an arena in which serfs and folk cultures might enter into new, often ambivalent or inverted relations of master and slave.[9]

Likewise, the “centrifugal force” he describes in these masquerade days pulls back from centralized power; it emphasizes the periphery over the throne. A serf could dress outside their rank in the costume of an aristocrat or king. Folk culture could use masquerades to impersonate and caricature power. These masquerade festivals provoked outbursts of laughter, which allowed for freer speech as well as more indignant articulations of dissent.

Masquerade’s function, therefore, might be conceived in manifold ways: to conceal one’s identity, to dance and celebrate, to wear the guise of another, to anonymize oneself, to critique society’s (constructed) rules, to act out deviant and nonconformist possibilities, and to propose an alternative structure for the world.

As with Reindorf’s earlier work, a relationship between body, dress, and architecture returns in her work at the Biennale, particularly in the sculptural installation Veil as part of the Mawu Nyonu project. This installation expands on her earlier masquerade costumes with the addition of the torso of a female figure, whom Reindorf names Lara.

In Veil, glittering cerulean beads cascade in concentric rings, suspended from the circular beams overhead. Their trailing forms delineate the boundary of a scintillating cloud, its edges hovering centimeters above the plush blue floor covering. Like an elaborate scaffolding, the hanging beads draw the eye inward toward the hollow, bronze torso of the female figure. In her fragmented form she appears like a piece of ancient statuary. Beads bedeck her waist, referencing both the history of glassmaking in Venice as well as Ghanaian clothing styles and practices of adornment in which beads often line the hips and waist.

The outer layers of these threads and glass beads, like fringe along the bottom of a dress, form walls around the figure. They take on an architectural dimension, shielding Lara behind a privacy screen and preventing a visitor’s hungry eyes from fully glimpsing or accessing the central figure; this occlusion and frustration of the viewer’s desire to know and gain access to the figure at the installation’s center enacts one aspect of the work’s strength. The installation invites visitors to journey through the hanging beads to the center “slowly, carefully, and quite laboriously.”[10]

In contextualizing the work, Reindorf discusses her intention behind the figure or “skin” she names Lara. “Mawu Nyonu is a fictional secret society more than an actual place and Lara is one of the characters that makes up Mawu Nyonu,” she writes. “The Lara character actively attracts and simultaneously repels, and this is achieved through the use of material that invites the observer, but never allows them to get close enough…. Lara is always depicted behind a wall, a veil, or a curtain, etc., in the paintings and these barriers in physical form add to this experience in person.”[11] Through the use of barriers and screens, Lara controls not only her own body, but the space surrounding it; she fills the room with her garment-as-architecture, impeding viewers and hampering their gazes.

Na Chainkua Reindorf, Lara: Mind Your Own, 2021–22. Acrylic gouache and cotton thread on Belgian linen canvas. 48.75 x 68.75 inches (123.8 x 174.6 centimeters). Image courtesy of the artist. Photograph by Na Chainkua Reindorf.

Surrounding Reindorf’s beaded installation, her series of paintings inspired by Asafo flags read as the loose signifiers of a community of state citizens and its seat of power. Asafo flags as fluttering semiotic devices host a visual record of proverbs and storytelling for the typically-male militias of the Mfantsefo, or Fante, people. Adorned with geometric patterning, cut fringe edges, and elaborately-quilted piecework and applique of soldiers and a phantasmagoria of beasts, each frankaa, or flag, includes an inset of another flag in its upper corner. From 1874 to 1957, this would typically have been the British flag under Ghana’s British colonial government[12]; a post-independence frankaa would instead show the Ghanaian flag’s black star.

In Reindorf’s paintings, neither colonial nor Ghanaian flag merits this distinction; rather, a diamond flag representing Mawu Nyonu dominates, its rectilinear form pierced by the curved lens of an iris. In combination, these forms constitute a glassy “unblinking eye” insignia at the corner of each painted frankaa. The eye observes the viewer and returns our gaze, much like the role reversal proposed in Reindorf’s earlier masquerade sculptures. By providing an alternative to the masculine and bellicose nature of the traditional Fante frankaa, Reindorf brings women’s issues to bear: What sort of proverbs would these “headstrong, individual, and unruly”[13] women tell? Which narratives would surface?

These paintings bear eponymous titles referring to their subjects. Gedu: You Have Changed, Tokpe: Friends Today, and Lara: Mind Your Own combine the names of Reindorf’s mythic figures with phrases drawn from their personalities. “This idea is inspired directly by the spirit-led masquerade communities in Western and Central Africa, where donning the costume imbues the wearer with the spirit of the masquerade,” Reindorf writes. “I am exploring this project through fiction and world-building and proposing that the costumes based on each of the seven characters also imbue wearers with their characteristics, where everything in the case is fictional but spills into the real world.”[14] Reindorf’s mythology and the character Lara are repurposed as allegorical figures to represent a woman’s autonomy, her right to secrecy, and the distinct forms of power she wields, informed by feminist arguments for bodily autonomy and the right to self-determination.

In their flattened planes and reiteration of the flag-as-art-object, Reindorf’s paintings also recall Jasper Johns’ well-known series of paintings, in most instances simply titled Flag (begun 1954). Johns began to produce these painted works during the Cold War years in the US. In them, shreds of newspapers are embedded in the pigment and encaustic wax surface of repeated representations of the US flag, producing questions of the simulacral basis of patriotism and the fact and fictions of national binaries bifurcating us from the other.[15] A later work by Johns, Flag (Moratorium) (1969) is punctured with a white hole as if pierced by a stray bullet; its colors are inverted in stripes of black and green with a pale orange rectangle of stars. Its reversed palette repurposes a children’s optical illusion to produce the afterimage of the US flag in the eyes of the viewer; upon staring at the image for 60 seconds and then looking elsewhere, the image would appear like a veil cloaking one’s vision with the image of the Stars and Stripes.[16]

Reindorf’s flag-based works are less direct, more evasive in their arguments, and therefore more generative. By situating them at the Biennale, they produce a secondary level of critique: the roles of patriotism and nationalism dovetail with Italy’s fraught history of fascist politics and its recent return in the right-wing election of the Brothers of Italy, but also produces moments of critique within the Classical traditions of Roman art and beauty which lend Venice its authority as a cultural capital, and the role of the Biennale itself as the primary example of a nationally-segregated art fair.

A Brief History of a Biennale

Authentic/Ex-Centric: Africa In and Out of Africa, curated by Salah Hassan and Olu Oguibe, took place IN 2001 at the 49th International Art Exhibition, La Biennale di Venezia.

Established in 1895, the Venice Biennale hosts a long and well-documented origin story, locating its predecessors in the salons of the national academies of fine art, the Expositions Universelles, and a series of exhibitions in the late 19th century, which intended to unify Italian cities behind the Italian state. Through these expansive exhibitions, Venice gathered artists and creators, visitors and viewers of all stripes.[17]

Venice began to nationalize its Biennale in the early 20th century by requiring nation states to finance their own pavilions.[18] During Mussolini’s ascent to power in October 1922, the Biennale grew apace with the Italian fascist state, offering prizes for artists whose work aligned with the regime; following a wartime hiatus, the Biennale returned in 1948, less than five years after Italy’s surrender and three years after the full defeat of Axis powers in World War II.

Ugo Mulas, Venice Biennale, 1968.

It was not until the Summer of 1968 that the nationalist structure of the Biennale was at last challenged. Student protests interrupted the festivities to oppose its commercialism and the ethics of unequal financial access for the national pavilions. Temporary pavilions and “collateral events” were opened outside the Giardini to provide additional space beyond the existing national pavilions.[19] As John R. Gold and Margaret M. Gold write in their history of Venetian urbanization Festivals and the City: The Contested Geographies of Urban Events, “National pavilions [have] critics who maintain that the buildings symbolise imperialism, support an anachronistic approach to art in a more integrated world, and proffer a model that favours certain nations over others … The fact that only Venice among art festivals now retains this exhibitionary form has become part of its unique attraction.”[20]

Meanwhile, most African nations have only established territorial roots in Venice in the past two decades. This took place following the 2001 Biennale during which Salah Hassan and Olu Oguibe became the first African curators to participate.[21] Today, Ghana and South Africa remain the only African countries in the Arsenale and, overall, just nine of 54 African nations have found a foothold among the Venetian cobblestones.[22]

Representing Ghana in the pavilion’s second iteration, Black Star – The Museum as Freedom is conscious of these national and continental conflicts. Reindorf’s work, especially when seen in combination with Simone Leigh’s installation at the US pavilion, might propose the architecture of national pavilions as a stand-in for a kind of nationalist costume. Taken together, their two contributions consider a means to expose and undermine the national pavilion through shifts in scale and the act of masquerade.

While Reindorf’s approach delves into the rich terrain of her own inventions—intertwining proscenium with glass-bead filigree, scaffolding with stitching, and façade with the phantasmagoria of the masquerade—Leigh, on the other hand, builds her installation on a foundation of archival material and historic artifacts.

Sovereignty

Simone Leigh: Façade, 2022. Thatch, steel, and wood, dimensions variable. Satellite, 2022. Bronze, 24 feet × 10 feet × 7 feet 7 inches (7.3 × 3 × 2.3 m) (overall). Courtesy the artist and Matthew Marks Gallery. Photo by Timothy Schenck. © Simone Leigh.

Leigh’s exhibition Sovereignty was curated by Eva Respini for this past year’s edition of the Biennale. Featuring her iconic ceramic sculptures of Black feminine hybridity, Leigh’s installation is realized through the forms of cowrie shells, domestic jugs, African and diasporic artifacts, vernacular architecture, and raffia thatching, which are used to construct monumental figures. Bronze works like Satellite and Sentinel (both 2022) tower overhead. Their forms are derived from the D’mba ritual masks of the Baga of Guinea and Temne of Sierra Leone, masquerade-like ensembles worn together with raffia dresses during marriages, funerals, and harvest festivals.[23]

Leigh, however, reconfigures these traditional masks within the history of colonial fetish and the Surrealist abductions of African traditions by Euro-American art history. She combines the D’mba artifacts’ forms with markers of time, like the satellite dish and the Sphinx—antiquity folded with futurity—and includes features that span authentic and erroneous readings of African culture, including early Black American material culture as well as the exoticizing examples of French imperial “possessions” epitomized by the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition and its pavilions. These structures were built by French architects in a fanciful medley of architectural styles and inscribed a French colonial fantasy over top of a brutal reality of state violence.

[1] “AFRICAN PAVILION DURING THE 1931 EXPOSITION COLONIAL DE PARIS FROM ALBUM BY MARCEL BRAUN,” NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SINGAPORE. [2] “CAMEROUN-TOGO GRAND PAVILION, EXPOSITION COLONIALE INT. DE PARIS 1931,” ARCHETYPE MAGAZINE.

In a rejoinder to this former colonial enterprise, Leigh’s installation clads the Palladian foundations of the US pavilion with raffia thatching, mimicking both Baga ritual dress and the Paris Colonial Exposition’s questionable renditions of West African and Pan-African identity.[24] This action, titled Façade (2022) transformed the US pavilion into a figure in costume, enveloped in the same garb once used to (mis)represent African nations.

Façade finds its domestic analog within the pavilion’s walls in a sculpture titled Cupboard (2022), which juxtaposes a large ceramic cowrie shell with a raffia thatched hut to articulate the form of a woman’s dress. Consider this alongside another work Leigh exhibited two years prior in her solo presentation with David Kordansky Gallery, Cupboard X (2020), which linked raffia garments and thatched roofs in an exploration of scale and monumentality that engulfed the vaulted space of the gallery.[25]

[1] SIMONE LEIGH, CUPBOARD, 2022. RAFFIA, STEEL, AND GLAZED STONEWARE. 135 1/2 × 124 × 124 INCHES (344.1 × 315 × 315 CM). COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY. PHOTO BY TIMOTHY SCHENCK. © SIMONE LEIGH. [2–3] SIMONE LEIGH, CUPBOARD X, 2020. STEEL AND RAFFIA. INSTALLATION DIMENSIONS VARIABLE, APPROXIMATE INSTALLATION DIMENSIONS: 142 X 370 X 190 INCHES (360.7 X 939.8 x 482.6 CM).

This entanglement of the architectural and sartorial proposes a monumental Black female body that exceeds the boundaries of architectural space. Through her references to Edgefield pottery, Leigh draws attention to the slave economy as a foundation of US history and culture, while also gesturing to the unfathomability, or opacity, of myth, allegory, and artistic creativity.

By obscuring and eliminating portions of the body—the features of the face, the distant visage of figures many times lifesize, the partitioning of a portion of a gargantuan body that is only glimpsed within the confines of the gallery—Leigh plays her own games of masquerade and transfiguration, allowing her subjects the autonomy and plasticity to step out of the frame and exist elsewhere.

In the context of Venice, then, one sees how both Reindorf and Leigh repurpose architecture, textile, and natural fibers to create fanciful recombinations of the world as it was, is, and might become. In both instances, these artists depict the boundaries of mythic space, using the traditions of masquerade to upset hierarchies and to laugh at the pompous presentation of national and institutional bodies in power.

Christopher Squier is an independent writer, curator, artist, and archivist, focusing on conceptual and research-based projects in a global arts context. His writing practice aims to emphasize and elaborate on the work of sculptors, sound artists, filmmakers, and new media practitioners. He is the editor of the forthcoming publication Carl/Karl: Three Takes on Heidenreich (Berkeley: Carl Heidenreich Foundation, 2023), for which he contributed an extended essay on the use of sound and silence in postwar German cultural practices, and is currently at work on an essay for the exhibition catalog to accompany Michel Gérard and Marina Tëmkina’s joint exhibition at the Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch in Issoudun, France, this summer.

-

Foster, Hannah. “Black Star Line,” BlackPast. March 9, 2014. Accessed January 17, 2023. ↩

-

Moudileno, Lydie. “Barthes’s Black Soldier: The Making of a Mythological Celebrity,” The Yearbook of Comparative Literature, Volume 62 (Bloomington: Indiana University Bloomington, 2016), 57–72. ↩

-

Barthes, Roland. “Myth Today: Myth as a semiological system,” Mythologies. Translated from the French Mythologies, 1957 by Editions du Seuil, Paris. Translation 1972 by Jonathan Cape Ltd. Selected and translated from the French by Annette Lavers. (New York: The Noonday Press, a division of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1957), 115–119. ↩

-

Barthes. Mythologies, 115. ↩

-

While much of the original image has in fact been misrepresented by Barthes in his eagerness to propose a semiological theory around French imperialism, a detailed comparison, as noted by Moudileno, reveals the facts: the “soldier” is barely ten or eleven years old; actually, he is the child of a soldier and he is attending “Les Nuits de l’Armée,” a spectacle at the Palais des Sports in Paris. And the French flag, although perhaps implied, is absent. Moudileno notes, too, that Barthes’ diction is regressive. His word choice for the “Black” soldier strikes English-speaking ears as an obsolete racism; by the time of his writing, the same word in French had already been deemed pejorative by Leftist academics. Examples abound of the switch to “noir” in theoretical writing, with Aimé Césaire by 1939, Jean-Paul Sartre in Orphée noir (1948), and Frantz Fanon’s Peau noire masques blancs (1952). ↩

-

Reindorf, Na Chainkua. “Screen: A Work That Looks Back,” May 2017. Copies on file with the author. ↩

-

Reindorf. “I Am (Not) Myself: West African Masquerade Tradition and the Construction of the Self”, Dissolve, Issue 3: Touch, February 28, 2017. ↩

-

Lachmann, Renate. “Bakhtin and Carnival: Culture as Counter-Culture,” Cultural Critique, Winter (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988–89), 117. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Reindorf. “Lara Installation Notes,” copies on file with the author. ↩

-

Reindorf. Email correspondence, copies on file with the author. ↩

-

Anderson, Shelley. “Asafo flags from Ghana,” Textile Research Centre, April 17, 2021. Accessed April 17, 2023. ↩

-

Reindorf. Email correspondence. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interestingly, when offered for sale by Leo Castelli Gallery, Johns’ Flag (1954–55) was considered “potentially ‘unpatriotic’” by MoMA’s Museum’s Committee and Board of Trustees. It was rejected from an acquisition proposal by the museum’s founding director, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. in 1958, and the work was only acquired by donation in 1973, following the transformation of HUAC (The House Un-American Activities Committee) into the House Committee on Internal Security, an action symbolizing the end of the era of political repression ushered in by Senator Joseph McCarthy.

See: “Jasper Johns, Flag, 1954–55 (dated on reverse 1954),” MoMA. Accessed April 17, 2023. ↩

-

See MoMA’s explanation of a similar work: “Jasper Johns, Flags, 1967–68, published 1968,” MoMA. Link ↩

-

Gold, John R. and Margaret M. Gold, “Chapter 9: Longevity and Reinvention: Venetianization and the Biennale,” Festivals and the City: The Contested Geographies of Urban Events (London: University of Westminster Press, 2022), 149–168. ↩

-

Ibid., p. 151. ↩

-

Ibid., p. 154. ↩

-

Ibid, p. 157. ↩

-

Hassan and Oguibe mounted the exhibition Authentic/Ex-Centric: Africa In and Out of Africa. At the same moment, Okwui Enwezor’s touring exhibition The Short Century: Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa, 1945–1994 brought the late yet necessary attention to European audiences of the breadth of contemporary artists working in Africa and across its diaspora. While Egypt was one of the earliest examples of a nation to join the Biennale, with its pavilion established in 1897, it remains the only African country with a pavilion in the Giardini today. Meanwhile, South Africa joined the Arsenale in 1950 but was banned during its Apartheid years.

See: Berns, Marla C. “Africa at the Venice Biennale,” African Arts, Vol. 36, No. 3, Autumn (Los Angeles: UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center, 2003), 1, 4, 8, 91–92, 96. ↩

-

Proctor, Rebecca Anne. “African Nations Are More Present at the Venice Biennale Than Ever—But Not Always on Their Own Terms,” Artnet News, May 25, 2022. Accessed April 17, 2023. ↩

-

“Baga D’Mba Mask,” Sierra Leone Heritage. Accessed January 19, 2023. ↩

-

Princenthal, Nancy. “Simone Leigh’s Sovereign Territory,” Art in America, May 4, 2022. Accessed January 19, 2023. ↩

-

“Simone Leigh, Exhibitions, May 25–July 11, 2020,” David Kordansky Gallery. Accessed January 19, 2023. Link ↩