The Anthrobscure: Earthworks, Coal Mines, and Michel Gérard’s Geological Investigations of the Underground

/detail of Robert Smithson, Asphalt rundown, 1969. Cava dei Selce, Rome, Italy. Asphalt, earth. Sculptural Event. CREDIT: Holt/Smithson Foundation

Historically, land art has been understood mainly in its connection to the crust of the earth and the soil beneath its surface. The object of an artwork is produced in the form of large-scale geometric figures, which are physically carved into the strata of the earth’s mineral deposits to unearth quasi-geological figures on its surface. These human interventions into landscape become creations akin to sublime phenomena—earthquakes, canyons, rifts, and sinkholes; natural landforms as well as archaeological structures within the landscape provide both model and substrate for the works of artists like Walter De Maria, Robert Smithson, Alice Aycock, or Michael Heizer, whose Double Negative (1969) bisects and reorders the mesas of the Moapa Valley in Nevada.

Heizer’s recently completed architectonic monument City (1972–2022) is emblematic of most current interpretations of the land art movement; it constitutes an earthwork of platonic forms and carefully-tuned pyramids, created on a massive scale and at an immense cost of time and labor—opening only recently in 2022, five decades after he began the project. City is a monumental imposition on a stretch of land that it has been argued would not be useful or productive for other purposes beyond art. Indeed, the standard features of the U.S. West populate the surrounding desert, where an Air Force base and a bomb-test site are already established and a proposed railway line was planned for transporting nuclear waste to Yucca Mountain; more recently, seven hundred and four thousand acres of wilderness surrounding City were set aside for preservation as a national monument under Barack Obama’s administration.[1] The prominence of government and military projects alongside Heizer’s City emphasizes the inaccessibility and complex jurisdictions around a number of these Western landscapes within which Land Art projects are situated, and which have too often been set aside as waste deposits, weapons testing sites, and otherwise “uninhabitable” lands and land-fills—landscapes which become closed sites of industry, military action, and postwar cleanup.

However, it should be acknowledged that many of these earthworks are situated in precisely the same supposedly “empty” landscapes, which were once populated by the Hopi, the Paiute, the Navajo, and numerous Indigenous peoples—landscapes which have been mythologized as neutral wastelands and stretches of desert, but were in fact dispossessed and seized in acts of settler-colonial violence. Today, their designations as government monuments, military bases, and records of Euro-American art history continues this co-opting of the land and its potential to serve as a site of history, memory, and memorialization for Indigenous people. As Assiniboine scholar Alicia Harris has demonstrated,[2] the history and institutionalization of Land Art has created a framework for these artworks in which they are understood as marginal and external, existing at a distance, rather than as place-based artworks. They exist in opposition to an idea of the specific, familiar, and inhabited landscape—what Harris terms a “homeland.” Similarly, their history is often severed from performative, activist, and concurrent art historical explorations of the land which operated on a more human scale, as with Ana Mendieta’s Silueta series (1973–80), Beverly Buchanan’s cast-concrete sculptures and monumental projects inspired by Southern U.S. architecture and landscapes, and the ecofeminist art movement of the 1970s. Land Art can be seen to continue the history of settler-colonialism within an imagined frontier by performing an erasure of Indigenous people, their histories, and the contributions of Indigenous artists. Similarly, art historical discourses continue the mythologization of these large-scale works, occluding and making obscure the presence of monumental histories and traumas within the Western U.S. landscape.

Michael Heizer, City, 1970–2022. Courtesy Triple Aught Foundation. Photo: Eric Piasecki

Earthworks like Heizer’s entrench themselves within the ground(s) of the desert, spreading across vast terrains and demanding visitors make pilgrimages under the desiccating heat and sun to remote plots of land. The land upon which Land Art projects are located, although initially purchased or rented by the artists, has been maintained for decades by major nonprofits like the Dia Art Foundation, the Noah Purifoy Foundation, High Desert Test Sites, and the Chinati Foundation.

As these artist interventions into/alongside the land find increasingly institutional footing, adapting from models of ephemeral intervention, propositions, and situations toward pilgrimage-ready art destinations, it is worth considering where these projects began and how the artists initially encountered these landscapes.

In this essay, I emphasize the importance of dirt and grease in what were seen as industrial and postindustrial landscapes rather than the often pristine landscapes associated with Land Art today—beginning with a description of Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, before examining the practice of Michel Gérard, which delves into the unlit recesses and sooty spaces of the earth that lie underfoot and beneath the earth’s crust. By attending to the earth and its material residue of industrial and war-torn histories, these works preserve a record of the twentieth century that is muddier and murkier than the well-known Land Art projects might at first suggest.

Incoherent Structures

robert smithson, spiral jetty, 1970. Great Salt Lake, Utah. Mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks, water. 1,500 ft. (457.2 m) long and 15 ft. (4.6 m) wide. photograph: gianfranco gorgoni, Building Spiral Jetty with truck and bulldozer, Great Salt Lake, Utah, 1970

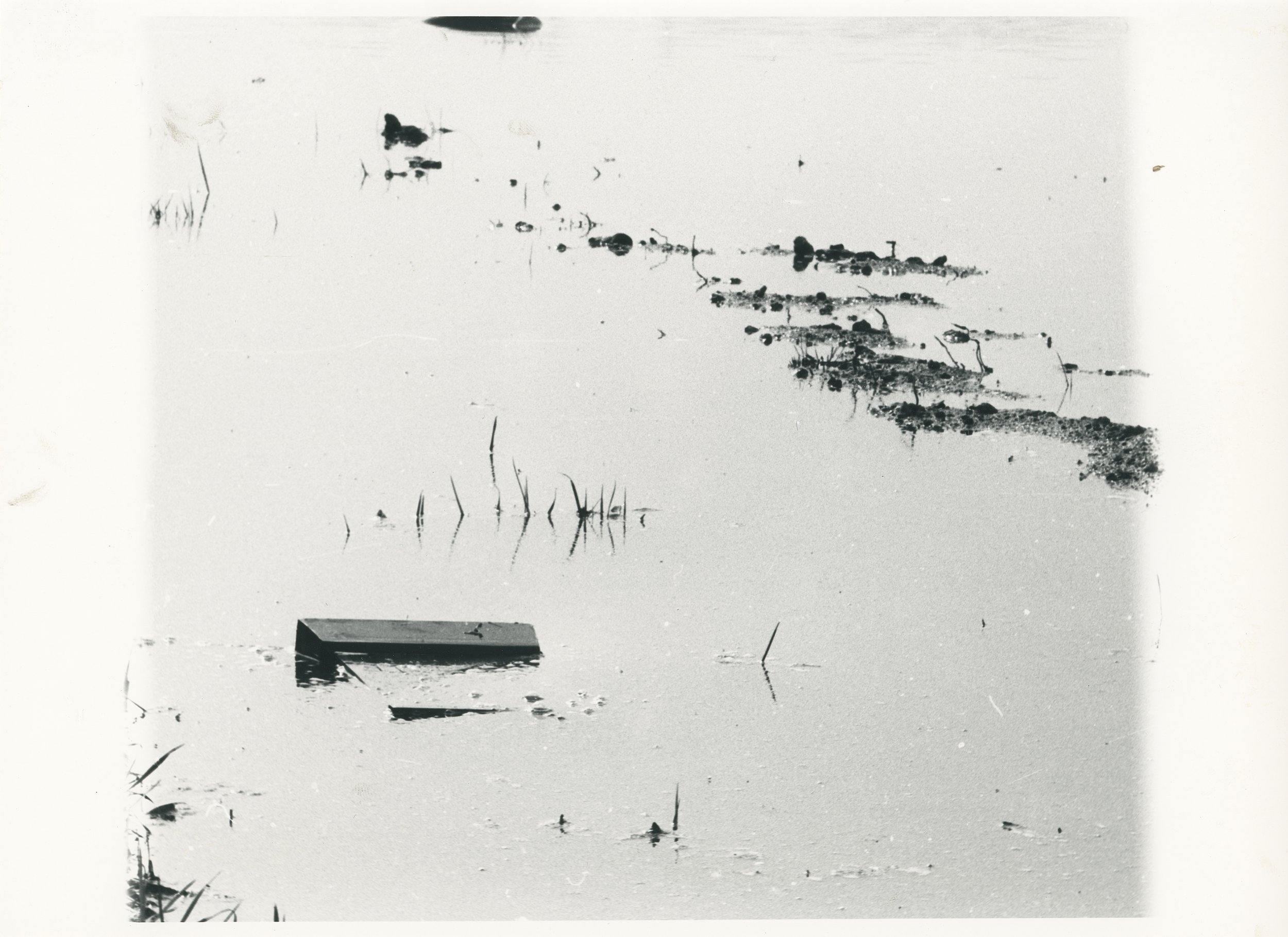

Robert Smithson’s account of visiting the land that became his project Spiral Jetty offers a sense of the artist’s awe at the expanses of time and space embedded in the long history and ancient strata of its site; he points to the prevalence of industry, mineral extraction, and industrial detritus in what has often been presented in sanitized images of the sublime:

“Slowly, we drew near to the lake, which resembled an impassive faint violet sheet held captive in a stoney matrix, upon which the sun poured down its crushing light. An expanse of salt flats bordered the lake and caught in its sediments were countless bits of wreckage. Old piers were left high and dry. The mere sight of the trapped fragments of junk and waste transported one into a world of modern prehistory. The products of a Devonian industry, the remains of a Silurian technology, all the machines of the Upper Carboniferous Period were lost in those expansive deposits of sand and mud. Two dilapidated shacks looked over a tired group of oil rigs. A series of seeps of heavy black oil more like asphalt occur just south of Rozel Point. For forty or more years people have tried to get oil out of this natural tar pool. Pumps coated with black stickiness rusted in the corrosive salt air. … A great pleasure arose from seeing all those incoherent structures. This site gave evidence of a succession of man-made systems mired in abandoned hopes.”[3]

Smithson’s account delves into the industrial and postindustrial conditions of the land, where the interplay of erosion by wind and water, corrosion under salt water, and pollution by human means combines. There is nothing picture-perfect here; rather, there is an “incoherence,” an illegibility which Spiral Jetty underscores through its vertiginous spiral against the vibrations of waves and punishing heat of the landscape, enabling a viewer to discern aspects of the shifting scales of the site: geologic periods caught in the strata and rock forms, visualizing time from the Silurian, Devonian, and Carboniferous; the expanse of salt flats, the decaying man-made structures, and the miniature activities of microorganisms—vivid red algae and bacteria, which occasionally turn pungent in the salt water.

The Underground

michel gérard, Averroës, 1976. dechromed sculpture. installation view. courtesy of the michel gérard studio

French-American sculptor and installation artist Michel Gérard was born in 1938 just ahead of the Nazi occupation of Paris in 1940. As a result, much of his work possesses a direct or tangential relationship to war, occupation, the unconscious, and bodily sustenance by means of its material and site-specific considerations.

As a young artist, Gérard became caught up in the spirit of the times. Echoing the activist and civil rights struggles across Eastern Europe and the U.S., May 1968 brought about a French student revolution, whose participants sought to overturn the traditional hierarchies of French society. Artists turned away from galleries and museums, bringing art into the street. Gérard participated in a collective action by artists who plastered anonymous posters throughout Paris with calls to democratize and rethink the country’s traditional political system. One of the most well-known of these posters bore the words, “Sous les pavés, la plage,”[4] demanding an unearthing of the landscapes and subterranean possibility beneath the bricks, pavement, and cobblestones of French culture.

Gérard spent much of the following decade musing on the successes and failures of this revolutionary period. His Socles and Grand-coffres (1976–78) present a series of sculptures representing damaged safes and pedestals. Their surfaces are pitted and cracked, their faces smashed and segmented; as a result, their upright stability is transformed into bloated, sagging, and empty vaults and plinths. Many of these sculptures are nameless, violently desecrated and left to oblivion; others bear the names of historical cultural figures through to those of the 1970s, from Ibn Rushd (often known as Averroës) and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel to Buffalo Bill and Yuri Gagarin. Some are photographed buried beneath the ground, covered in soil or sand in a funeral rite of former cultural ideals.

MICHEL GÉRARD, SOCLES, 1976. CHROMED, DECHROMED, AND COPPER SCULPTURES. INSTALLATION VIEW. COURTESY OF THE MICHEL GÉRARD STUDIO

Gérard’s work frequently intervenes into the public realm and the various sites of the urban and post-industrial landscape. In the context of postwar conflict, recovery, and revolution, Gérard’s work can be seen to call into question and to oppose the dehumanizing conditions of a traumatic and bellicose world while seeking to repair the damaged social tissue of his generation.

At the same time, Gérard’s works embrace the premise of “the underground,” as artistic and social change-bearers are frequently termed. As a site of its own, the underground, subsumed in soil, strata, and darkness, can serve to dislodge hierarchies and hegemonic structures. In his drawings, installations, and sculptures, Gérard displaces the meaning of the work to this site of the underground, whether in semiotically remote, psychologically repressed, visually obscured, or physically-buried contexts, to emphasize the critical importance of these places in the formation and recovery of individual identity and collective movements.

These concerns of the 1960s counter-culture would resurface in Gérard’s work throughout the following four decades. At the same time, his works began to develop a set of dialectics of matter/alchemy, the terrestrial/constellatory, and the earth through its presence as dust, soot, and particulates in an otherwise gaseous and immaterial atmosphere.

The Anthrobscure

My argument builds on the notion of media geology and media archaeology as defined by the new media theorist Jussi Parikka, among others, to propose a geo-politics as geological politics in an extension of the more typically formalist earthworks of land artists made between the 1960s–80s. In this context, Gérard’s experiences as a child of World War II and an immigrant to New York who brought with him sensitivities to conflict, care, hunger, and sustenance, can be understood to lead to a series of artworks that were deeply engaged in questions of the developing Anthropocene, defined by the intertwined crises of ecological devastation and increasingly global “forever wars.” In their excavation of the earth’s interior, specifically in its coal mines and oil wells, Gérard’s artworks venture into the underground to consider the earth as a form of media.

Parikka has drawn links between the work of land artists like Robert Smithson and the theories of media geology and media archaeology, interdisciplinary studies which bring into contact communication technologies and the infrastructural networks of visual and technological media[5] with artistic practices investigating the soil, ground(s), plate tectonics, and interlinked systems of the earth and its ecosystem.

Looking to Smithson, Parikka references his term “abstract geology” as a precedent for a philosophy of tectonics and geophysics as they “pertain not only to the earth but also to the mind.”[6] For Smithson, abstract geology was a way of theorizing the body and psyche, using geology and the processes of earth, land, and wind to rethink the anthropocentric limits of the self. Erosion, crystallization, fragmentation, decomposition, and grit could be applied to ideas of the ego and id.[7] It is a radical reorientation of how we relate to our environment and understand ourselves.

Parikka defines the role of the subterranean within media geology, writing, “The grounds, ungrounds, and undergrounds of media infrastructures condition what is visible and what is invisible.”[8] Here, Smithson’s formula of abstract geology might be inverted to consider the undergrounds of the city as the psychological depths of culture and civilization.

Training our eyes on the unlit and obscured spaces of industry and power might lead us to reconsider what surfaces in hyper-visible spaces (or stages) of public discourse that appears to be clean, clear, and self-apparent, while asking us in turn to attempt to navigate the murkier, often intentionally-obscured sites of labor, memory, and political expression.

Toward this aim, I propose a new term insisting on the enforced obscurity of “post”-industrial processes and movements forced underground: the “Anthrobscure” describes a period in which ecological devastation meets the long-term denial of consequences stemming from the exploitation of the earth’s resources. Mirrored in Gérard’s darkly-pitted Black Drawings and roughly textured sculptures of post-industrial spaces, one can understand the Anthrobscure as an era of optics, spin, and obfuscation which aims to conceal and smother clarity in smog and haze, burying information and stratifying collective movements. Rearticulating the Anthropocene as a visual (and often invisible) experience which leans toward darkness and depth, the Anthrobscure plays games with vision (darkness, omission) and language (illegibility, incoherence) to recontextualize the ground on which we stand and the activities playing out above and below us. In Gérard’s drawings and installations, then, one might recover an archeological impulse unearthing the post-industrial landscape to envision a profoundly dystopian, industrial nightmare for the earth.

Coal, Coke, Schist, Anthracite

michel gérard, ouranos, 1988. installation: coal. Gaillac, France. courtesy of the michel gérard studio

Gérard, who relocated to New York City in 1990, began invoking the materials and themes of geology in the late 1980s and 90s. In a series of installations and sculptures that engage with the movement of Land Art, he responded to a moment of drastic transformation of U.S. cities and landscapes at a time when New York, Pittsburgh, Syracuse, and other industrial sites underwent abandonment and decay. It was an emerging post-industrial era of overseas labor—what architectural scholar Keller Easterling has termed the “human cloud” of migrant workers and part-time laborers—moving industry out of cities and exporting unsavory industrial factories, pollution, and waste from capitalist, consumer-culture nations to other zones, which concentrate and market production and labor.

Throughout the 1980s–90s, Gérard engaged with the syntax of earthworks, the post-industrial landscape, and the legacies of extractive mining through the use of coal as a material and in depictions of the dark spaces of mines and metal forges in which spiraling marks animate nearly-indecipherable backgrounds.

Works like Ouranos (1988), installed in Gaillac, France, resurfaced coal, coke, and schist from beneath the bucolic lawn of the Château de Foucaud in termite-like mounds and priapic outbursts. Subsequently, the installation was destroyed by bulldozers after the protests of the local population against foreign laborers. While it existed, the installation was formed of seven eruptions of coal in towering cones. They punctured the verdant surface of the château’s lawn in a perfect diagonal, seemingly marching in step toward the imperious architecture of the house. The intervention pierces the surface of the lawn to undermine the appearance of civility and tidiness, unearthing the presence of a black carbon seam in the French landscape. By making visible a landscape that is tied to industry, energy, and labor, Gérard also draws attention to a geopolitics of wealth and excess. While the Château de Foucaud has become a public site of leisure, industrial labor persists at a distance; the contracting of immigrant or migrant labor is perceived as dirty, undesirable, and an imposition upon the French economic system.

michel gérard, cross-section, 1989. mixed media including forged steel, burnt branches, leaves and plants, charcoal, coke, schist, shale, and anthracite in progressives sizes, sampled from the La Mure mines in Isère, France, with 42 forged steel elements. centre d’art contemporain du creux de l’enfer, thiers. courtesy of the michel gérard studio

For his solo show at Mannheim Kunsthalle, Gérard created an installation titled Havage (1987), made of a chain of forty forged metal wheels surrounded by coal, a fragment of industrial excavation and transportation. This interlinking chain represents the cutting and hauling mechanism for coal mining, but also creates an abstract diagonal line, which extends like a drawing across the gallery space. Scattered chunks of charcoal refer both to the transformation of wood and organic debris into mineral and stone and, as with a charcoal utensil, refer to the act of making marks on, and into, the land. Perhaps industry can be said to be the most invasive form of art, marking the land with a complex contour drawing.

Havage was followed by another installation, Cross Section (1989), of a coal mine extracted and laid horizontally across the surface of the gallery floor at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, the capital of coal mining in the United States. The installation presented stratum by stratum the transformation of materials from leaves and burnt branches, plants, charcoal, coke, schist, shale, and anthracite in a diagramatic visualization of geologic strata. The exhibition space became a way of looking beneath the surface of things. By reordering biological materials, detritus, and heavier stones in a telescopic view of the matter beneath the earth’s crust, Gérard’s installation underscored the alchemy of geologic materials: how one material might exist momentarily as animal or vegetable before transmuting into stone or returning to soil. Here, alchemy in its transformation of materials is made even more definite than in Havage; depth and the underground is made accessible through the simple idea of a shift in orientation, so that increasingly ancient geologic periods are exposed by walking along the edge of the installation. In the Pittsburgh Post Gazette and the Tribune Review, journalists wrote of his work as “'a postmodern archeology of industry,'”[9] “dark and brooding,” which “against the pristine white walls of the gallery [weaves] in subtle drifts of leaves.”[10]

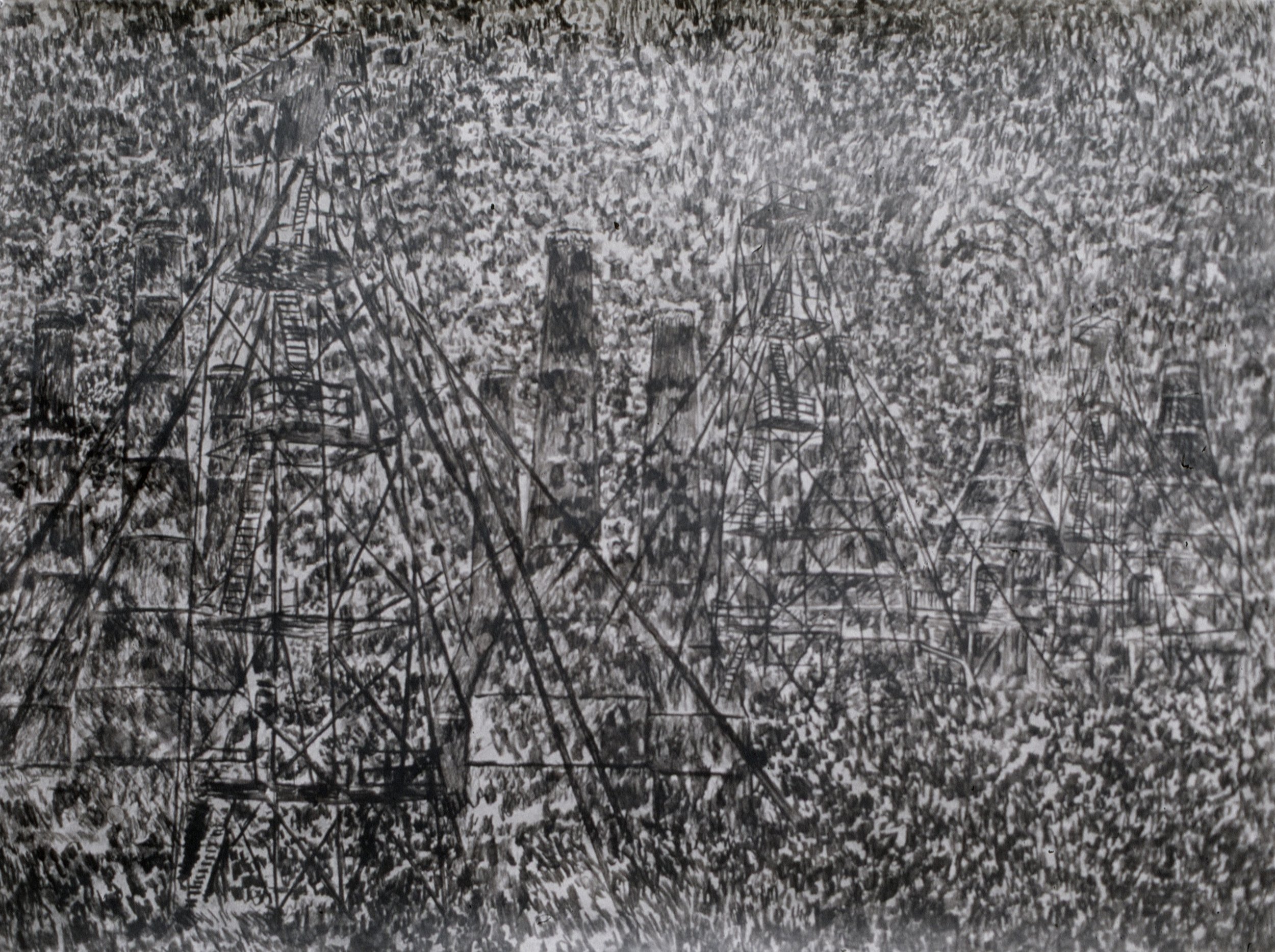

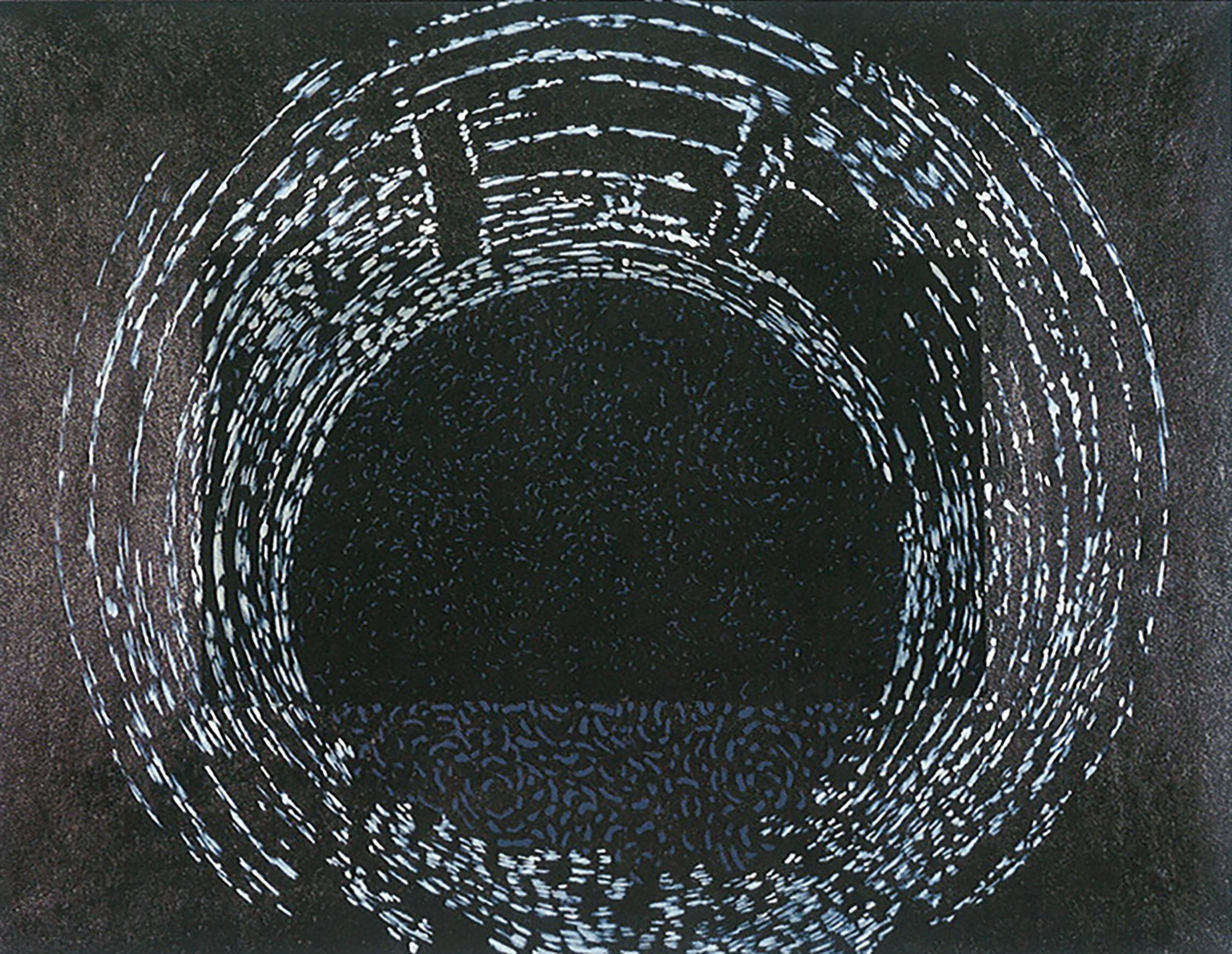

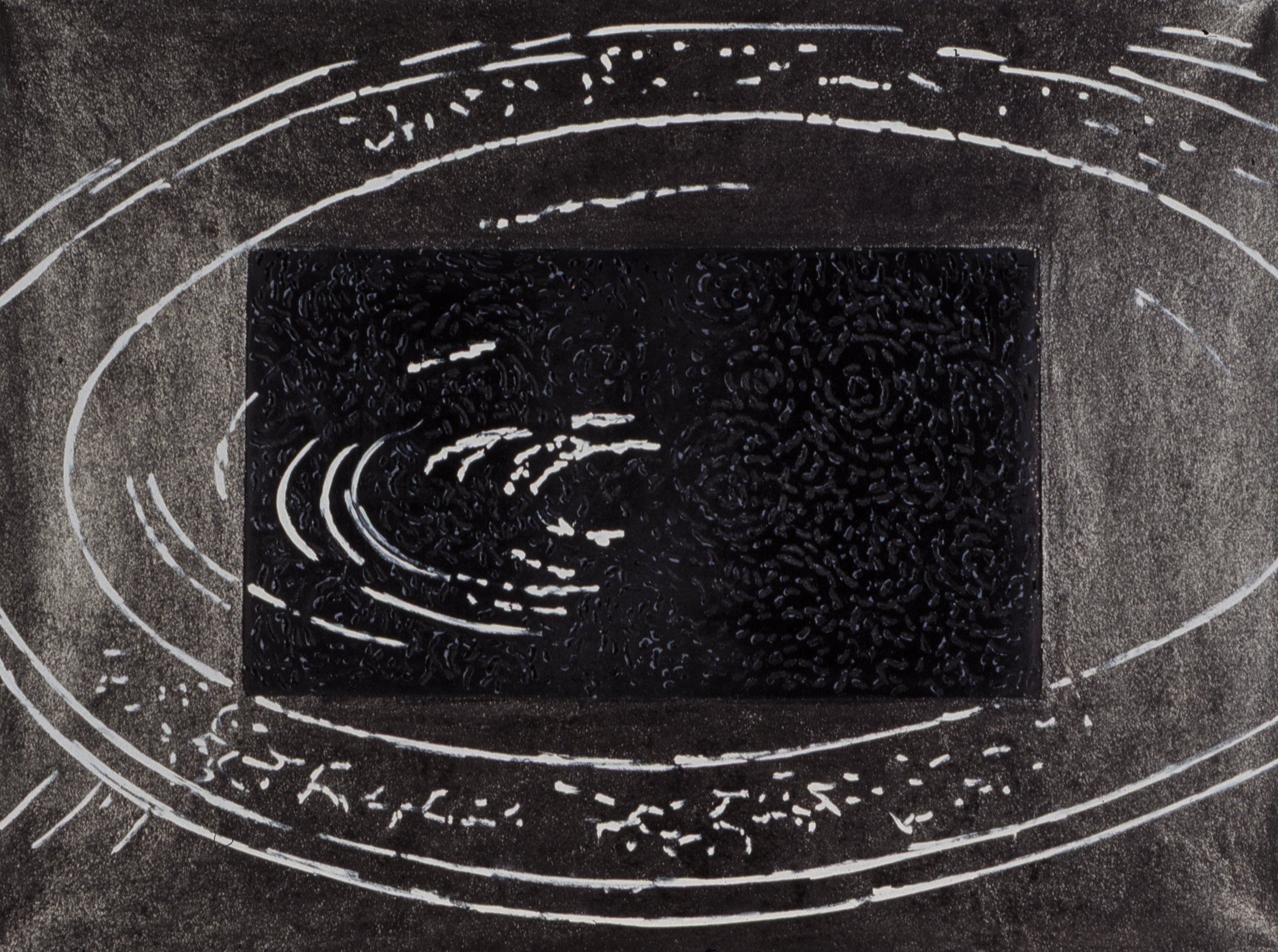

MICHEL GÉRARD, VIEW THROUGH THE PIT, 1988; UNTITLED (BLACK DRAWING), 1989; UNTITLED (BLACK DRAWING), 1991; VOYAGE AU CENTRE DE LA SAAR, C. 1989; AND VOYAGE AU CENTRE DE LA SAAR, C. 1989. CHARCOAL AND COAL RUBBED AND PASTED ON PAPER. 135 X 100 CM EACH. COURTESY OF THE MICHEL GÉRARD STUDIO

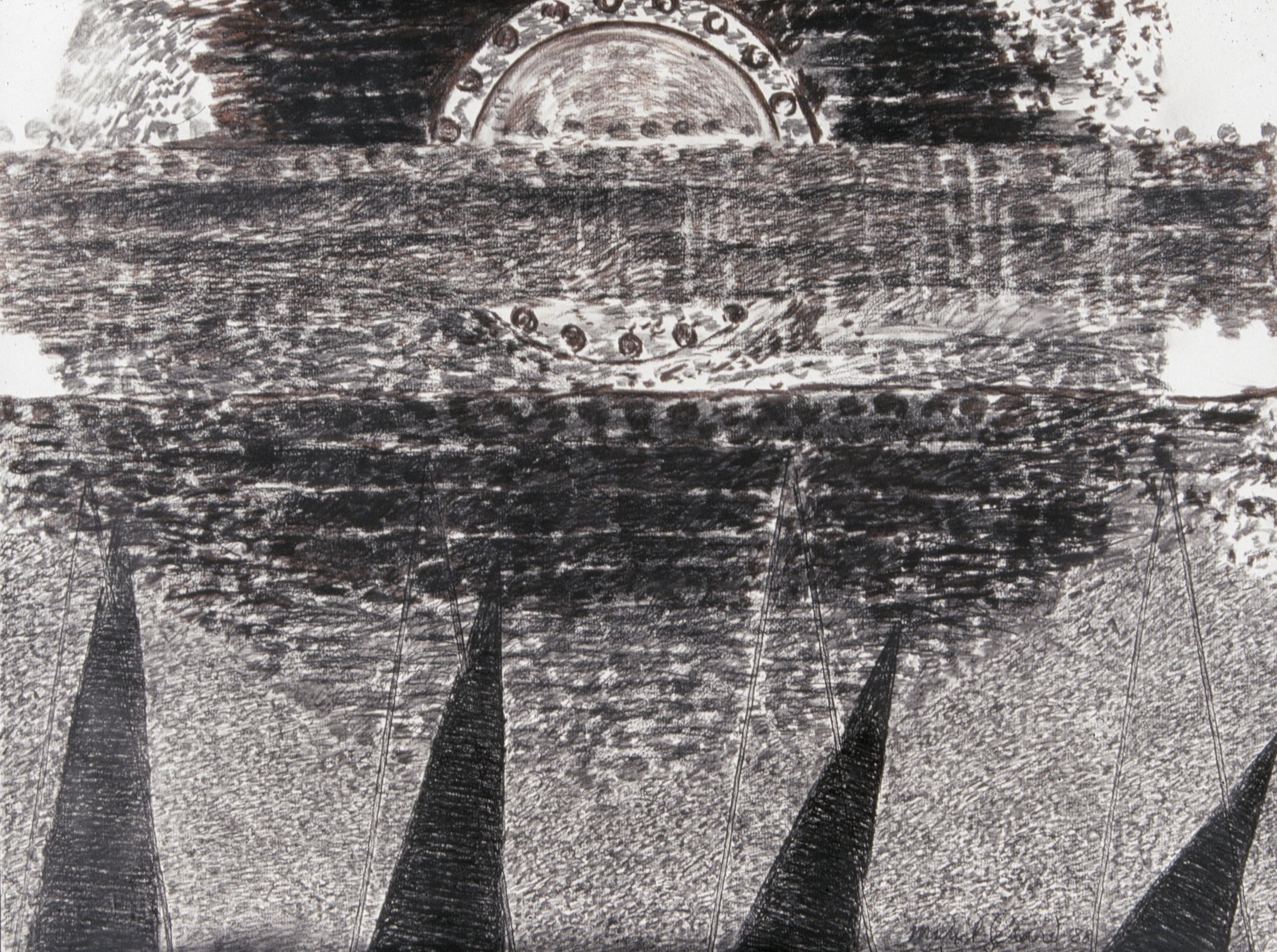

Alongside these installations, Gérard created a series of black charcoal drawings featuring images of the depths of the mines, machinery, and darkened tunnels used for the extraction of coal. These drawings of deep brown and black subterranean spaces visualize the near total darkness of metal forges and mines, whether of mining tunnels or aboveground factories and foundries. The work vibrates with the energy of geologic spaces lit by the sparks of heavy industry. These drawings rendered in charcoal, pencil, and occasional pastel are almost obliterated by the darkness of their surfaces. Staccato marks spiral rhythmically in cloudlike charcoal vapors. Jagged, amorphous streaks obfuscate the surface. This obscurity conceals and reveals. The rough forms of mechanical and industrial devices, both recognizable and invented, appear in threes in a dreamlike repetition: three observation towers surrounded by smoke stacks; three train cars chugging out of the frame; three silos belching pyramids of coal—always repeated as if a moment of deja vu or a fairy tale spell.

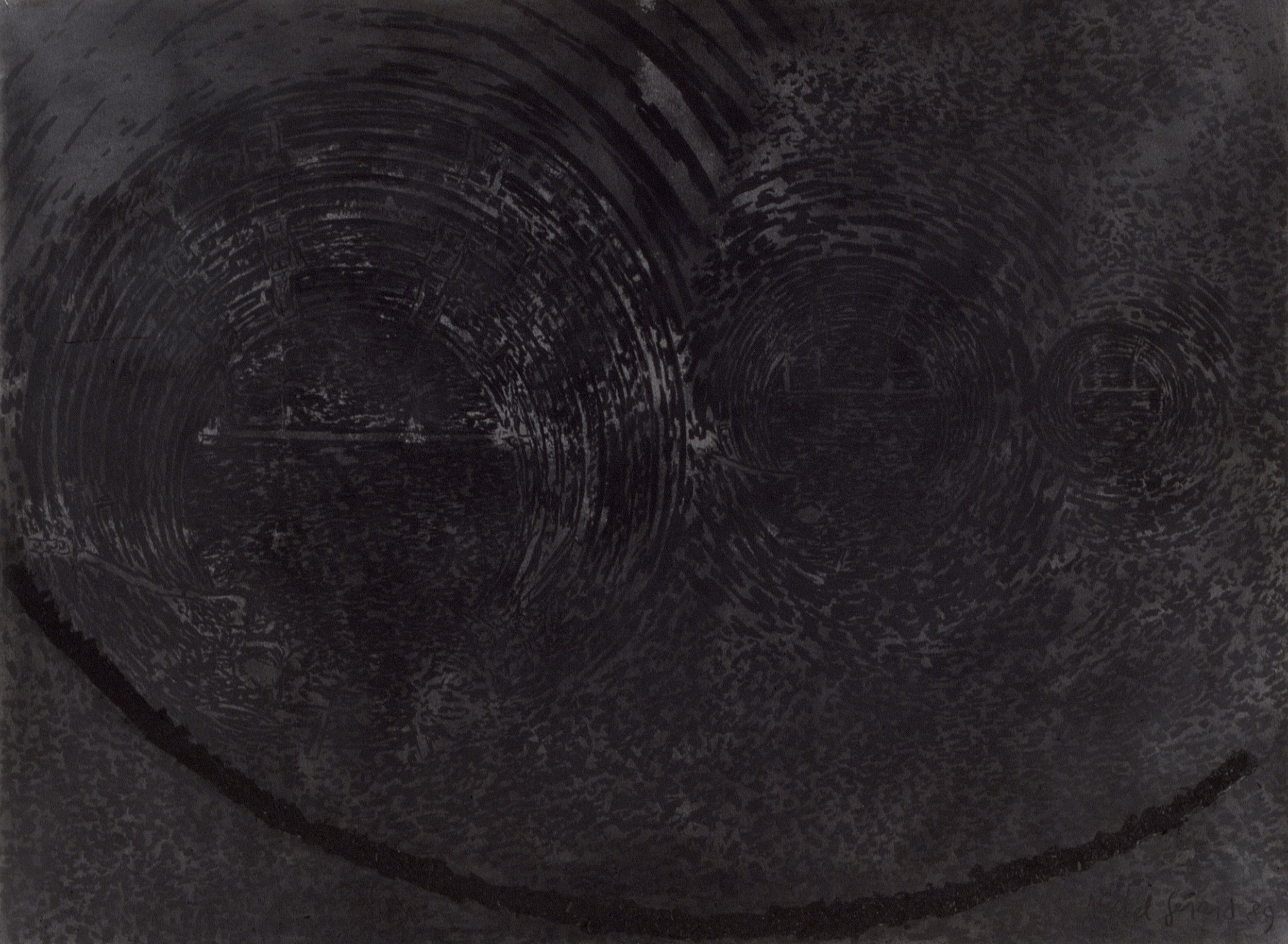

Similarly, mixed media drawings like a series of four large works titled Migrating Particles (1991) are formed from industrial materials in the act of creation. The works’ surfaces scintillate with reflective aluminum powder suspended in a black glue, which covers the linen canvas. Carved rubber rectangles are embedded in the center of the work: a frame within a frame. Various degrees of darkness persist, receding and projecting from the composition’s perspective structure. The one-meter tall works are painted with fractured lines of white oil paint, which depict, variously, a receding circular tunnel, a mushrooming twister or atomic explosion, and a set of parallel ellipses that progress diagonally across the surface.

MICHEL GÉRARD, MIGRATING PARTICLES, 1991. OIL PAINT, GLUED ALUMINUM POWDER, AND ENGRAVED RUBBER ON CANVAS. 100 x 135 x 6 CM EACH. COURTESY OF THE MICHEL GÉRARD STUDIO

These drawings can be said to be full of particulates: small particles of soot, dust, powder, and other matter that drifts and spirals in the air of mines. Media geology draws on Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of “the metallurgical” as a form of minor science “that teases out the potentialities in matter.”[11] For Deleuze and Guattari, this is given in opposition to the hylomorphic model of materiality, in which matter is inert and inanimate. In Gérard’s drawings, the animation and force of particulate matter floating in the atmosphere and obscuring vision is made palpable. Especially in the context of underground landscapes, these “dirty” spaces of industry, labor, and pollution remind us of the dichotomies of space: sanitized above ground and polluted below.

This same principle can be understood as a dialectic arguing against notions of progress, in which the earth is developing toward a cleaner, greener future; instead, Gérard’s work suggests that pollution continues to waft from below, refusing to settle and stay put. As Parikka reminds us, “The underground is the place of hell—itself defined in Western mythology by its chemistry: the smell of sulfur, and the killing poisons of carbon dioxide, which is why since Virgil’s Aeneid the Underworld is marked by death to any animal approaching it. The underground is at the crux of [the] technological imaginary of modernity.”[12]

Petroleum

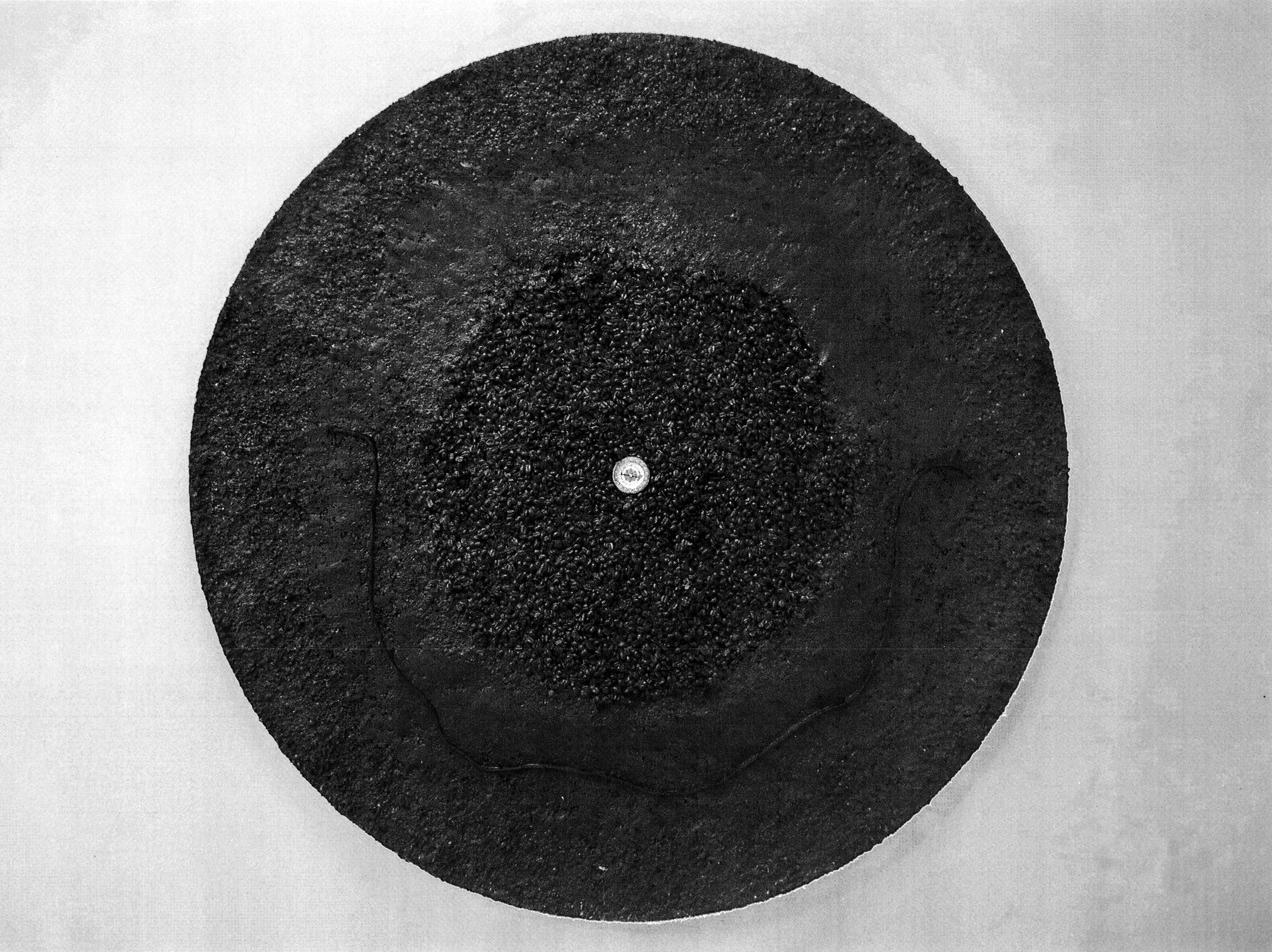

MICHEL GÉRARD, PERSIAN RUG, 1991–95. mixed media: wood, earth, steel, aluminum, fox fur. 200 CM IN DIAMETER. COURTESY OF THE MICHEL GÉRARD STUDIO

In 1990 and 1991, triggered by Iraq’s invasion of the Gulf state of Kuwait, the U.S. led a coalition of 35 nations in the military action Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm that became known as the Gulf War. At stake was geological matter below the Earth’s crust—oil. The extraction of resources became a flashpoint for television viewers around the world. In an eruption of violence that lasted just over a month and decimated both Iraq and Kuwait, the Gulf War made visible the resources of the subterranean earth as critical resources upon which human livelihood depended. Oil fires burned for weeks, while immense ecological damage ensued.

As news of the environmental devastation spread, Gérard began work on a new sculpture that collapsed these realities of ecology, geology, drilling, and war. Persian Rug occupied Gérard from 1991 until 1995, during which time he built, revised, and added various materials to an over six-foot diameter tondo representing the desiccated, scorched landscape of the Persian Gulf War.

The result is a mappa mundi of current politics and potential global futures, as well as a mandala of sorts: a circle of earth drawn to contemplate the world beyond. The sculpture, a circular disc layered with cracked red earth and pitted with steel inclusions like oil drilling sites, comes across as a Martian landscape, perhaps the red planet in a distorted future, excavated for its material resources and mineral wealth. Then the reality hits: this is our planet. The extractivism of our world in microcosm is clear, a world which abandoned its surface to the ravages of militarism, industrialism, and desertification.

It serves as the afterimage to a familiar zeitgeist today: the Martian colony of space industrialists, the arid uninhabitable expanses of Dune or Blade Runner, the inhospitable climates of a deserted dystopian future. However, in Persian Rug this vision descends closer to the depths of hell, ringed by an apocalyptic halo of a blackened fox’s skin. Enfolding the work in a literal cadaver, the fur, face, and feet of the animal offer a desperate elegy for an already-forsaken world.[13] Whether as a vision of current events or a prefiguring vision of today’s science fiction futures, the world Persian Rug represents is bleak and unforgiving.

Similarly, the forms of Gérard’s other sculptures from this period are geometric, abstract at first, but the materials are familiar, perhaps even homely in their reference to domestic space. Couscous, lentils, paprika, matchsticks, and coffee are alchemized into a sculptural material in the form of a thick paste akin to the rough texture and sturdy matte finish of stucco. Many of the pieces are darkly textured, pitted, and amorphous landmasses. Their discs can be understood as planetary terrains.

MICHEL GÉRARD, FRENCH ROAST, 2011; COFFEE BEANS, ACRYLIC, COMPASS, ROPE, GLUE, WOOD. NIGHT NAVIGATION, 2012; COFFEE BEANS, STEEL, WOOD, ACRYLIC, GLUE. DESERT MONSTER, 2012; SAND, EARTH, BRANCHES OF TREES, ACRYLIC, GLUE, WOOD. FIRE ELEMENTS, 2012; PAPRIKA, ACRYLIC, MATCHES, GLUE, WOOD. COURTESY OF THE MICHEL GÉRARD STUDIO

One work, French Roast, takes the form of a 46-inch diameter disc made of coffee beans, acrylic, a compass, rope, glue, and wood; these materials take on an earthy appearance like loam. The dark surface of the sculpture is achieved through covering and impressing coffee grinds and whole beans into acrylic and glue.

Within Gérard’s practice, the work harkens back to the darkly scintillating spaces of coal mines and shafts. Equally, this disc is a kind of landmass, a territory as seen from above. In its circular form, it can be understood as both a globe and map. Embedded in its center, a compass points outward, gesturing toward an undefined elsewhere. Night Navigation offers a similar glimpse of the darkness and pitted surface of a dusty, earthen planet.

In total, we might see Gérard’s oeuvre at the core of a conversation about the ways we see and, especially, the ways we conceptualize the finite terrains of the earth—not so much as an immense, unchanging, and stable landscape into which artists might mark their place for future generations, but rather as a damaged ecosystem which is fragile, susceptible to human forces, and marked by industry, human conflict, soot, and the obscurity of the underground.

Christopher Squier is an independent writer, curator, artist, and archivist, focusing on conceptual and research-based projects in a global arts context. His writing practice aims to emphasize and elaborate on the work of sculptors, sound artists, filmmakers, and new media practitioners. He is the editor of the forthcoming publication Carl/Karl: Three Takes on Heidenreich (Berkeley: Carl Heidenreich Foundation, 2023), for which he contributed an extended essay on the use of sound and silence in postwar German cultural practices, and is currently at work on an essay for the exhibition catalog to accompany Michel Gérard and Marina Tëmkina’s joint exhibition at the Musée de l’Hospice Saint-Roch in Issoudun, France, this summer.

-

Goodyear, Dana. “A Monument to Outlast Humanity,” The New Yorker. August 22, 2016. Accessed September 12, 2022. Link ↩

-

Harris, Alicia. “Įknáʾotąʾį: Medicine Wheels, Mounds, and Maps: Ancestral Indigenous Land Art.” pp. 1–7; “Reframing the Land Art Narrative,” pp. 14–35. In “Homescapes: Indigenous Land Art and Public Memory,” dissertation, University of Oklahoma, 2020. Accessed November 28, 2022. Link. ↩

-

Smithson, Robert. “The Spiral Jetty (1972)” in Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’ Writings. Edited by Kristine Stiles and Peter Selz. (University of California Press: Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: 1996): 530-33. ↩

-

“Under the pavement, the beach.” ↩

-

Here, referring to television, email and its predecessors, the heavy metal and mineral components of smart phones, and the submerged fiber optic cables of the internet. ↩

-

Parikka, Jussi. A Geology of Media, Electronic Mediations, vol. 46 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015): 5. ↩

-

Smithson, Robert. “A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects” (originally published in Artforum, September 1968). Accessed on January 5, 2023. Link. ↩

-

Parikka, A Geology of Media, 30. ↩

-

Miller, D. Article for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. ↩

-

Both from B. Homisak's article for the Tribune-Review. ↩

-

Parikka, A Geology of Media, 22. ↩

-

Ibid., 14. ↩

-

Although not present in early photographs, the fox fur was included in the sculpture in 1995 in a foreboding final touch. ↩