Between Development and a Hard Place: The Future of a Diverse Artistic Community in Oakland

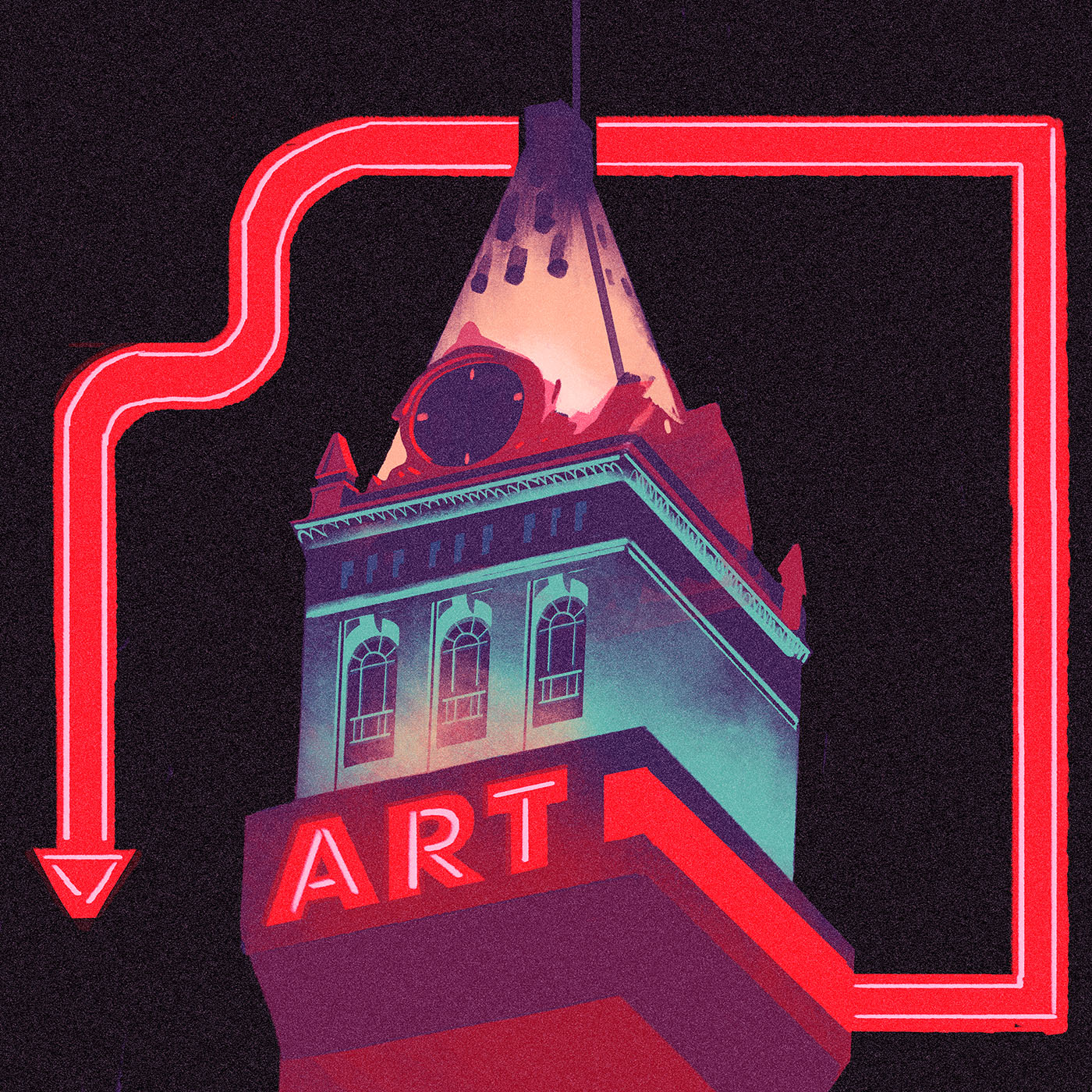

/"Oakland Tribune", Ryan Johnson, 2016.

Since the early 2000s, Oakland has become known as a bastion of affordability for artists seeking refuge from the high cost of living in San Francisco. A 2014 New York Times article, “Oakland: Brooklyn by the Bay,” called it a “welcoming oasis,”[1] even though at the time of the article’s publication, Oakland was experiencing one of the fastest rising rents in the US, beating out both San Francisco and New York.[2] The article’s language and timing point to the seeming contradiction that many established and burgeoning artistic communities face: establish a strong community of artists and displacement will likely follow.

Because of their need for inexpensive housing and work spaces, there is a long history of artists sharing urban spaces with marginalized communities. Coinciding with the move of artist into urban cores during the 1960s after deindustrialization and white-flight, was the emergence of new social programs that sought to reengineer the urban landscape to accommodate the flow of capital and attract an upper middle-class consumer culture. Such programs used artists and the cultural activities that take place around them as vehicles for redevelopment and exclusion. Thus, as Martha Rosler succinctly puts it, artists are in the position of being both “perpetrators and victims in the process of displacement and urban planning.”[3]

To a degree, artists are complicit in how they impact the urban spaces they choose to occupy—a relationship that is far too complicated to cover in the space of this article. Yet their potential role in gentrification is arguably peripheral to much deeper histories of intentional inequality, wrought by targeted institutional and cultural disinvestment in urban neighborhoods throughout America. Part of the issue of having a more meaningful dialog about arts-based gentrification, is that “the arts” are often lumped together linguistically. In fact, “the arts” encompass a range of both commercial and community art practices and a diverse range of participants that can have radically different relationships to the communities they operate within. A 2014 report funded by the NEA, “Gentrification and the Artistic Dividend: The Role of the Arts in Neighborhood change,” found that while commercial galleries moving into economically depressed neighborhoods is a clear indication of rising income inequality, locally-driven art initiatives have the potential for both the economic and social revitalization of existing communities.[4]

In Oakland the general characterization of the arts as a cohesive whole has become an impediment to thinking critically about how best to support the continuation of a diverse artistic community. For example, the city has put a great deal of its focus on its First Friday events, which characterizes itself as an, “immersive community art experience.”[5] The monthly street festival, which attracts 10,000 - 20,000 visitors to the downtown/uptown area, has played a critical role in establishing Oakland’s image as a creative metropolis. Yet the event has arguably done more for developers and the city’s plan to transform Oakland’s economic backbone than it has to support local artists and arts organizations.

Since 2013, First Fridays have been managed by Koreatown Northgate (KONO), a group of property owners along Telegraph Avenue between 20th Street and 34th Street. The group has not been shy about the event’s impact on redeveloping the area. A 2014 economic impact report, published on the KONO and First Friday websites, cites increased revenue on event days for both vendors and local businesses, such as bars and restaurants. The report also cites the event’s value to real-estate companies as a means to entice new residents and investors.[6] The many shops and businesses that have opened doors in the last few years on and near the downtown Telegraph area, are clear indicators that the neighborhood is changing quickly to accommodate a more affluent consumer class.

Contrary to First Fridays, Oakland Art Murmur, though often conflated with Oakland First Fridays but operates as its own 501 (3)(c), is currently questioning its longevity. Initially started in 2006 by a group of eight artist-run collectives and galleries in both the Temescal and Northgate neighborhoods, Art Murmur—initially called First Friday Art Walks—was meant to pool a collective audience in an area that didn’t yet have an established art community. Yet none of the original eight Art Murmur participants remain. The last holdout, Rock Paper Scissors, which offered low-cost art classes to the community, was priced out of its location on 23rd and Telegraph in late 2015.

An open letter “Save Oakland Art” by Art Murmur’s Board of Directors and published in February by the East Bay Express, warns that should the downtown area continue to rapidly develop, the arts will be forced out. The letter noted that in 2015 three of its member galleries had shuttered their doors—Rock Paper Scissors collective among them—and many tenants were experiencing a forty to fifty percent increase in rent. The letter also pointed out that while the city has been willing to give tax breaks to attract new businesses—particularly tech corporations— they have merely played “lip service to the arts,” and have done little to invest long-term in Oakland’s creative community.[7]

Another victim of the rising inequality in downtown Oakland is Betti Ono Gallery, a black women-led and operated community art space invested in Oakland’s underrepresent communities. For the past five years the gallery has been located on 14th and Broadway in a city-owned building, but in late 2015 Betti Ono was notified that their rent would increase by sixty percent—an additional $22,00 a month.[8] In reaction to the rise in rent and potential displacement, Betti Ono launched their #LovePowerResistence campaign to raise the $50,000 necessary to stay in their current location, and has been unsuccessfully petitioning the city to provide them with a long-term lease.

Betti Ono’s location, which borders Frank Ogawa Plaza and is easily accessible from the 12th Street BART station, is significant to the organization’s mission to be a space for community activism and organizing. Their proximity to City Hall—the center of local power—means the organization has more direct access to local officials and city operations, in order to make visible the plight of Oakland’s most vulnerable artistic communities. To combat wide-spread displacement, Betti Ono’s director Anyka Barber, along with Katherine Canton of Emerging Arts Professionals, co-founded the Oakland Creative Neighborhoods Coalition (OCNC).[9] OCNC’s #keepoaklandcreative campaign has advocated for better representation of Oakland artists and their communities at the local-government level. [10]

Ultimately, what organizations like Betti Ono understand, as well as many within the Oakland artistic community, is that the crisis afflicting Oakland’s most vulnerable creative members, is a crisis of housing. To better understand and advocate for equitable housing in Oakland, Betti Ono partnered with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project to create the “Oakland Community Power Map.”The map, which is accessible online, allows participants to chart important cultural and community spaces throughout the city. The hope is that the map can be a tool for housing advocates to identify potential cross-community partnerships, and build new coalitions against displacement.

The public practice exhibition at the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA), Oakland, I Want You to Know… also aims to open up cross-community dialogue around displacement and housing in Oakland. Specifically, the exhibition examines the changing economic and cultural landscape of West Oakland, which has been one of the most embattled sites of development given its close proximity to San Francisco. For the exhibition OMCA commissioned artists and community organizations to create a network of residents through projects that engage visitors in questions of belonging, community, and cultural identity.[11] Visitors are urged to take action and write letters to Oakland council members, asking them to protect Oakland’s long-term residents and prioritize anti-displacement measures.

The displacement facing artists and arts organizations has not gone unnoticed in Oakland’s City Hall, yet the solutions put forth offer no real long-term systemic solutions to support an equitable artistic community. In 2015, current Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf convened a task force to consider ways to better support the arts, and in August 2016 she appointed Roberto Bedoya to serve as the city’s first cultural affairs manager.[12] In 2015 Oakland’s City Council amended a 1989 Public Art Ordinance, to require developers to set aside one-percent of construction costs for public art.[13] However, the amendment has already met opposition among developers, who are currently suing the city over the tax, claiming it violates constitutional property and free-speech rights.[14]

Pressuring the city to tax corporations for the arts is a step in the right direction, but doesn’t go far enough to actually support local artistic activities. In her widely cited work, Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics , Roselyn Deutsch notes that the ascension of public art in New York accompanied increased privatization of public space.[15] While government commissioned artworks funded by private development might make for an aesthetically pleasing city, they also point to a corporate makeover of downtown Oakland. Public art, and the 1989 tax ordinance, are hollow gestures towards the arts that, in the long-term, will likely continue to benefit the very developers who are opposed to it.

No single tax measure will solve the problems afflicting Oakland’s artistic community—or its underrepresented communities, for that matter. Low-income housing, long-term leases for arts organizations, and more equitable forms of granting to artists and organizations working within their communities, are desperately needed. There also needs to be a general shift in funding priority. While Oakland artists and organizations struggle to keep their lights on, institutions such as SFMoMA, which raised over $300 million for its expansions and added another $245 million to its endowment, arguably does very little in the long run to support a local community of artists.[16] Part of this shift requires a better understanding of how different sectors of the arts either support artists and the communities they are embedded in, or add to the increasing economic and social inequalities reshaping the urban landscape.

It is easy to imagine Oakland becoming a city with all the glitz of corporate sponsored public art, but unable to actually sustain a local community of artists. In 2017 Uber will open the doors of its new headquarters on Broadway and L. Berkeley Way, across the street from one of Oakland’s newest murals painted by Jet Martinez. These two blocks seem to represent the frightening future of art in Oakland if things do not drastically change in the immediate future: murals and public art that adorn corporate-owned buildings, adjacent to new luxury condos that occupy the streets that once had the potential to support a thriving artistic community, but are now the after-work play area of the economic elite.

-

Haber, Matt. “Oakland: Brooklyn by the Bay.” The New York Times. Published May 2, 2014. Accessed September 3, 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/04/fashion/oakland-california-brooklyn-by-the-bay.html?_r=0 ↩

-

Kolko, Jed. “For Home Prices, The Rebound Effect is Over. Long Live Job Growth.” Trulia. Published February 10, 2016. Accessed September 3, 2016. http://www.trulia.com/blog/trends/trulia-price-rent-monitor-jan-2015/ ↩

-

Rosler, Martha and Brian Wallis. If you Live Here: The City in Art, Theory, and Social Activism. Seattle, Wash: Bay Press, 1991. 31. ↩

-

Grodrach, C., N. Foster and J. Murdoch III. “Gentrification and the Artistic Dividend: The Role of Arts in Neighborhood Change.” Journal of the American Planning Association 80, 2014. 3 – 7. ↩

-

“About.” Oakland First Fridays. Accessed September 27, 2016. http://oaklandfirstfridays.org/ABOUT ↩

-

Swift, Victoria. “Economic impact of Oakland First Fridays.” Mills College. 2014 https://www.scribd.com/fullscreen/199399474 ↩

-

Oakland Art Murmur Board of Directors, “Save Oakland Art.” East Bay Express. Published February 24, 2016. Accessed September 10, 2016. http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/save-oakland-art/Content?oid=4688437 ↩

-

Burke, Sarah. “The Fight to Save Betti Ono Continues.” East Bay Express. Published March 31, 2016. Accessed September 10, 2016. http://www.eastbayexpress.com/CultureSpyBlog/archives/2016/03/31/the-fight-to-save-betti-ono-continues ↩

-

Burke, Sarah. “Will Oakland Lose Its Artistic Soul?” East Bay Express. Published February 17, 2016. Accessed September 10, 2016. http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/will-oakland-lose-its-artistic-soul/Content?oid=4679618 ↩

-

“Downtown Oakland Specific Plan.” City of Oakland. Public draft published March 1, 2016. Accessed October 1, 2016. http://www2.oaklandnet.com/oakca1/groups/ceda/documents/report/oak057387.pdf ↩

-

“Oakland Museum of California Presents Exhibition Exploring West Oakland’s Social, Economic, and Demographic Shifts, Generating Community-Driven Discussion Around Gentrification.” Oakland Museum of California. Published June 28, 2016. Accessed October 1, 2016. http://museumca.org/press/oakland-museum-california-presents-exhibition-exploring-west-oaklands-social-economic-and ↩

-

Hemmelgarn, Seth. “Gay Poet to Oversee Oakland Cultural Affairs,” The Bay Area Reporter, published, September 1, 2016, accessed October 22, 2016. http://www.ebar.com/news/article.php?sec=news&article=71851 ↩

-

Johnson, Chip. “Big Legal Guns Take Aim at Oakland’s Public Art Requirement.” San Francisco Chronicle. July 27, 2015. Access date: October 21, 2016. http://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/Big-legal-guns-take-aim-at-Oakland-s-public-art-6408586.php ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Deutsche, Rosalyn. Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics. Chicago, III: Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, 1996. 57. ↩

-

“Capital Campaign Fact Sheet.” San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. ↩